Use a total cost of ownership approach to optimize value when purchasing equipment and support services

Maximizing value during the procurement of equipment assets and raw materials is critical to the business functions of companies in the chemical process industries (CPI). Today’s tough economic environment places added pressure on chemical engineers to secure the best value for money spent on design and equipment. Whether the items your company needs are chemicals, pieces of equipment or skid-mounted packages, the focus should be on maximizing the total value of the item over its full lifetime, rather than on finding the lowest initial price. For example, a great purchase price for a heat exchanger may turn out to be a poor value if the materials of construction do not provide the required corrosion resistance.

One approach to thoroughly assessing the value of an asset for purchase is to use a total cost of ownership (TCO) analysis. This article explains how to conduct a TCO analysis, and how that information can be used, along with other strategies, to prepare for and conduct negotiations with suppliers in equipment purchasing transactions.

The TCO approach

Undertaking a TCO analysis involves two general steps: gathering raw data on the offerings of different suppliers, including price, reliability, expected lifetime and customer support; and then assigning a weight to each aspect of the equipment, according to its value and importance to your company’s particular situation.

The TCO approach positions a company for negotiating with suppliers to maximize the longterm value of equipment, supplies and services, even in cases where an item might have a higher initial pricetag.

A TCO analysis helps to account for all costs associated with a purchase, including tangible ones that appear at the time of acquisition (hard costs), as well as those that come into play later (soft costs). Hard costs would include price, shipping, installation and spare parts, while soft costs might be maintenance support services, training and amount of downtime. Soft costs, which can sometimes be more important in the CPI, are often overlooked in budgets — a situation that can lead to unexpected cost increases, or worse, projects that miss their start dates or processes that have critical quality problems.

The TCO approach allows both your company and the supplier more flexibility in negotiating terms and fees. For example, if the length of the service contract for a vacuum pump is more important to your company than the size of the fee, then the supplier can offer higher overall value to your company by providing a longer contract as part of the deal — raising its standing in the TCO analysis. This also helps create a win-win situation where the supplier can realize a price increase while your company gets the longer service contract, which may be a key consideration.

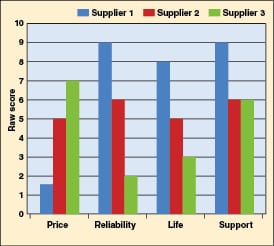

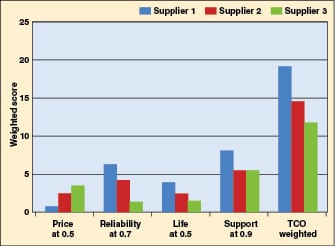

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate an example TCO analysis. The raw numbers offered by various suppliers in price, reliability, life and support are multiplied by the weighted values assigned by the company based on their importance. For example, if a total onsite service availability for a low-temperature cooling system has a weighted value of 0.8, and the vendor scores a value scale of 8, its net value is 6.4 (0.8 × 8). This means that the better service availability of the higher-priced machine could outweigh the lower price of a competitor’s machine with less service availability. In the hypothetical case shown here, buying from Supplier 1 would result in the highest weighted value overall, despite the fact that it charged the highest price.

Engage procurement early

In developing a TCO model and preparing to negotiate with suppliers, your organization’s procurement, purchasing or buying department can serve a vital function in helping to maximize value. By viewing the procurement specialists as a resource, and engaging them from the beginning of the process, you will enable them to help you develop your TCO model. Working with procurement up front can improve understanding of how commercial aspects of a transaction mesh with the engineering analysis.

In addition to helping with the TCO model, procurement personnel can also help you direct effective questions to suppliers, as well as recommend alternatives and evaluate supplier bids as you prepare to negotiate. Then, when the order is placed, procurement will expedite the process. If procurement employees are kept in the dark until a request for purchase is complete, they may not be in a position to help, and they are less likely to view the project favorably, since they were not involved in its progression.

Involving procurement personnel early may require a change in company culture because most engineers and stakeholders consider their knowledge of the process and equipment to be significantly greater than that of the procurement specialists. On the other hand, many procurement professionals believe that engineers are more concerned with getting the project completed based on their personal preferences and don’t always look at lower cost alternatives. Both groups need to understand the other’s strengths and recognize the power of working together. Working together begins with considering open-ended questions, such as whether engineers would be interested in an alternate supplier that could cut costs by 25%.

If you wait until the end of the purchasing process to involve procurement specialists, they will face pressure to “extract” a savings — usually by lowering price — when the deal is virtually done. At this point, most variables have been decided and the procurement department may feel forced to persuade or haggle. Involving procurement personnel as soon as the scope of work or specifications are discussed will help ensure that multiple variables are in play.

One organization in the midwestern U.S. familiar to the author has been particularly effective in fostering interaction between procurement and engineering departments. The engineering group on that site had been trained to inform the procurement department of any new contact with a vendor. The two procurement officers for this large site (3,000 employees working on multiple processes in multiple buildings) would then contact the prospective vendor and assist the purchasing engineer throughout the process, advising him or her about the procedures.

At every step, the procurement group was informed about any subsequent conversations regarding specifications or costs, and asked for comments. As a result, the organization was able to bring its other experiences into play and help the engineers ask the right questions and gather the correct information. Vendors and engineers who didn’t comply had a hard time getting their projects through on schedule.

Interview users

To properly weigh values as part of a TCO analysis, it is imperative for engineers to interview internal users of equipment. Once the weighted scale of importance is applied to the hard and soft costs, the results can lead to the correct procurement decision. Some examples of good questions to ask internal users are the following:

• Why is that particular quality important to you?

• What are your main priorities in purchasing this item? (This can help develop a weighted scale of the various hard and soft costs)

• What would be the consequences if we were unable to find the item with a particular characteristic?

• Under what circumstances would you agree to consider supplier B? (if supplier B had a poor delivery history, then you might put reliable delivery on a higher weighted scale)

• What consequences would result if the supplier refused one or another of our requests?

Using the answers to these questions, you can then identify the requirements for weighting a scale of both hard and soft costs.

Analyze the balance of power

The next part of preparing for any significant negotiation is a thorough analysis of the balance of power. When working with an internal client or colleagues, you need a robust and creative process. First, identify your company’s strengths and weaknesses relative to those of the supplier. List what you believe the supplier wants and what your company wants. Then plan your objectives, opening statement and strategy.

The next step is creating a wish list that includes items that would be nice to have as outcomes of the negotiation, but are not the focal point of the negotiation — perhaps better payment terms, a 24-h service hotline and a specific engineering contact in the organization. The wish list should be accompanied by a concession list of items in areas where your company is willing or able to sacrifice — maybe faster payment terms or a requirement to include the supplier’s engineering staff on quarterly capital-spending review meetings.

When your power balance analysis reveals that the supplier has more bargaining power, enter the negotiation armed with a series of proposals. Then drive the process by putting proposals on the table without spending too much time talking with the supplier. Be ready to ask what needs to be done to a previously rejected proposal to make it acceptable. This will help keep you and your company on the offensive while you stick to the agenda.

For example, if a supplier of a skid-mounted equipment package has allowed its prices to erode to preserve market share, you could both agree on the value scale categories. Then, by allowing the supplier to maintain or even increase price, you can demonstrate that, with other attributes, the total cost of ownership is less than other suppliers and you’re improving the original terms. Additionally, it may allow the supplier to use the “take away” method, where actions typically taken by the supplier are eliminated to influence the price category, as long as they don’t skew another category in the wrong direction. So if the supplier normally paints its equipment with a two-coat epoxy used in salty, humid areas, and you plan to install the equipment in the high desert, you might offer to the supplier the chance to use a less-costly paint and use the savings to lower the selling price.

Often, the internal partners within your own company who request equipment or material are quick to give in to terms to get the need fulfilled. This weakens your position and may create an unfavorable imbalance of power. Whenever you allow yourself to be put under time pressure, the other side gains more negotiation power because he or she can simply wait for you to change your position to get the deal done on time.

Prepare effective RFPs

Your role as an engineer is not just to specify equipment, but also to think like a buyer and consider information from both vantage points. Using the TCO approach will help identify key questions when developing a request for proposal (RFP) and interviewing possible suppliers, so you can place the proper value scale on the potential categories.

When working in a competitive bid process, make an RFP as specific as possible to arm yourself with more power by structuring the supplier’s expectations. Always think about what information should be disclosed to the supplier. Failing to reveal certain facts could work against you and lead to uninformed responses to your request. For example, if your company had recently been fined for a hazardous-chemical vapor leak from a heat exchanger and was facing severe fines for future leaks, you should explain the situation carefully so the vendor can understand the value you will put on this point. Prepare plausible answers that are clear enough to support your position without revealing sensitive information, such as the amount of the fines.

In this case, longterm corrosion resistance might have a weighted value of 0.9 (on a scale of 0 to 1). If vendors know that, they can address your value proposition correctly and try to score higher in that category. If the vendor performs well in this area, they will improve their weighted score to 9 (10 × 0.9).

Negotiate for value

When negotiating with suppliers, engineeers in the CPI must balance their attention between price and value — they can’t be too narrowly focused on price and forget about value, or vice versa. As the economy slowly recovers, many suppliers that have cut their prices deeply are now looking for increases. That means CPI engineers should be aware of different strategies for accurately valuing the products their company needs and obtaining them cost-effectively.

In some situations, you may be able to persuade a supplier to concede in certain areas or exploit leverage from a competitive situation, but those approaches are time-consuming and yield limited results. For example, if you’ve gotten competitive bids for a two-stage vacuum pump from four suppliers, you could use them against each other to push down the price. But if you persuade the supplier to lower the price to complete the deal, they may cut corners elsewhere, such as offering a more limited package of support services.

Structure expectations. During the negotiation process, structuring the expectations of the supplier correctly can be crucial to maximizing value for your company. Generally, it is beneficial to explain the qualities your company is seeking, rather than leaving the vendor to guess. Remember that vendors don’t have crystal balls and aren’t mind readers. Allowing the supplier to guess your needs may result in a long process before the two parties arrive at a proposal that your company is comfortable accepting. But by structuring expectations, you increase the likelihood that the supplier’s first proposal will be closer to your ideal position.

For example, if you have a specific budget that cannot be exceeded, do you tell the supplier up front or wait for a bid to come in? If you reveal this up front, the vendor may be able to package a proposal that meets your budget requirement, but at the same time allows the vendor to obtain additional value in other areas, such as supplying a longterm service contract or multiple years of recommended spare parts. If the budget ceiling is not revealed upfront, the vendor’s price may come in high and you will need to get the person to change his or her mind or lower the price.

Be ready to explain additional information to the other side, as long as it helps you clearly structure the supplier’s expectations in the right direction. So by telling a vendor you have multiple qualified suppliers, you’re structuring expectations that he or she will need to provide your company with good value to be selected.

Any information that may lower or minimize the other party’s expectations gives you more bargaining power and should be revealed early on, even if not requested. If the supplier is reluctant to share information, you can trade information that you deem important for other information that the supplier wants from you, such as the total potential business your company might offer.

Ask open-ended questions. In negotiations, ask open-ended questions designed to induce the other side to provide more detailed information. If you’ve been dealing with a supplier for a long time, through multiple rounds of negotiations against commodities or services that have remained constant over time, its margins may be nearing a limit. You may have gotten the best price on a particular heat exchanger, programmable logic controller (PLC) system, pump or raw material. But this supplier may have manuals, online tutorials and service plans that could add a level of value to your plant engineering and service personnel — which may be more important than the purchase price. In this case, you should use provocative questions like, “Under what circumstances would you [the supplier] provide what I am asking for?” For example, the supplier might have an online tutorial on Type 21 pump seal change-out that your maintenance staff could use. So it may be a good idea to ask under what circumstances you could get access to the tutorial.

If you’re considering several suppliers, reveal that to a vendor — but if, internally, your team believes that this vendor’s equipment is best, keep that information confidential.

Propose first. In cases where the TCO model is relatively simple, you know the market pricing, and there are few variables, such as the purchase of a readily available bulk-chemical commodity, you may want to make the first proposal to the supplier. The worst that could happen is that the supplier says, “Yes,” leaving you to wonder what you left on the table. But if you are happy with the deal, move on and sharpen your pencil for the next transaction.

Add value. Another useful technique for negotiating is known as the “add on,” where bare-bones, stripped models are quoted to meet the low-cost category, and you must ask for specific items to be included based on their importance and value scale. This enables you to start with a low price and then add value back in specifically where it is needed to meet the requirements of your company’s internal users. This technique will also allow the internal user to be involved in the process while seeing the cost and value of the required specifications.

For example, if you were specifying a process chiller, you could start with an indoor, water-cooled, standard electrical, no-process pumps specification. After receiving bids, you could ask for all of the above — but you could do so one at a time, as equipment options, until you have built the package that is best for your company’s situation. Usually, the seller will quote the lowest price on the base package and offer the best price for each option, thinking that each successive option will be the one to close the deal. In this way, you can then build up the package to the level you want or need based on the costs.

If you’re considering leasing equipment, then leasing would need a high relative value in the TCO process. In some cases, the total leased price over the full contract length could be less expensive on the surface, but would be offset by extension costs or equipment-replacement costs. So in this instance, it may be better to purchase a piece of equipment that seems more expensive on the surface, but comes with lower additional costs.

TCO helps reach company goals

Turbulent economies demand that we continually seek value in buying and selling. The TCO process can better position you and your company to maximize results. It will help you defend why, for example, you might not be purchasing the least expensive heat exchanger, PLC, or pump from a purely price-tag perspective — as you explain the critical value proposition.

When you begin to look at total cost of ownership, you may be able to partner more closely with the supplier to meet your monetary goals, and just as important, maintain the guiding principles of your plant, process and maintenance professionals.

Further reading

1. Fisher, R., Ury, W. and Patton, B., “Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In.” Revised ed., Penguin Group (USA) Inc., New York, 2011.

2. Harvard Business Essentials Series. “Guide to Negotiation.” Harvard Business School Publishing Corp. Boston, 2003.

3. Cheverton, Peter and van der Velde, Jan., “Understanding the Professional Buyer: What Every Sales Professional Should Know About How the Modern Buyer Thinks and Behaves.” Kogan Page Ltd., London. 2010.

Author

Rich Waldrop is vice president of Scotwork (NA) Inc. (400 Lanidex Plaza, Parsippany, NJ 07054; Website: www.scotworkusa.com; Email: [email protected]; Phone: 973-428-1991), the N. American div. of Scotwork Negotiating Skills, the world’s largest independent provider of negotiation skills training and consulting. Waldrop brings 25 years of experience in manufacturing and engineering, working in areas such as production, inventory control, sales and finance. He is a former member of AIChE, APICS and ASHRAE and current member of ASTD and IACCM.