Both physical security and cybersecurity must be in place to keep chemical facilities safe from attack

While almost all businesses in today’s world are concerned with security — both physical security and cybersecurity — chemical processors likely have a deeper interest, because the industry has been identified by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS; Washington, D.C.; www.dhs.gov) as a potential target for terrorism. As a result, chemical processors that are considered high risk according to DHS criteria must adhere to regulations put forth by the department’s Chemical Facilities Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS; see also Chem. Eng., September 2009, pp. 21–23).

According to DHS, the CFATS program identifies and regulates high-risk chemical facilities to ensure that they have security measures in place to reduce the risks associated with certain high-risk chemicals. Initially authorized by Congress in 2007, the program uses a multi-tiered risk assessment process and requires facilities identified as high-risk to meet and maintain performance-based security standards appropriate to the facilities and the risks they pose. On December 18, 2014, the president signed into law the Protecting and Securing Chemical Facilities from Terrorist Attacks Act of 2014 (“the CFATS Act of 2014”), which reauthorized the CFATS program for four years. It is expected that DHS will continue the program in the future, as well.

CFATS

“CFATS was initially developed over concerns that an individual or group could breach the perimeter and infiltrate a chemical facility with the intent of damaging storage vessels holding toxic materials, so the first step was to understand, at each of these facilities, where the chemicals were stored and then to create an outer perimeter with security that would prevent a saboteur from getting to these areas,” explains Joe Morgan, business development manager of critical infrastructure with Axis Communications (Chelmsford, Mass.; www.axis.com/us/en). “This cultivated the need for physical barriers and detection methods at chemical facilities and brought into the light the fact that chemical processors face larger and more significant threats than some other industries.

“Since then,” he continues, “it has been realized that physical security interacts with cybersecurity, because if someone were to hack into a chemical plant’s mainframe and gain access to processes via control networks, they could just as easily perform the same type of sabotage. So physical security and cybersecurity are becoming closely intertwined.”

Adrian Fielding, global marketing director, integrated protective solutions, with Honeywell Process Solutions (Houston; www.honeywellprocess.com) agrees: “The physical security and cybersecurity relationship is very symbiotic. You need one to protect the other. You need physical security to prevent someone from getting on site and into a server room and causing a cyberattack internally, and you need cybersecurity to prevent someone from hacking into a security system and taking critical systems down.”

Therefore, protecting just one or the other is not enough, says Jay Abdallah, global director of cybersecurity solutions at Schneider-Electric (Andover, Mass.; www.schneider-electric.com). “Securing one area is not sufficient, as the weakest area can be penetrated, causing a breach. All areas must be equally secured, using a combination of multiple detective and preventive controls.”

Threat vectors

But before a chemical processor can secure the facility, it is important to know the threats from which they require protection.

In the past, most chemical facilities had some sort of physical perimeter, such as fencing, for safety purposes to keep people from entering the property, says Darin Dillon, business development manager, with Convergint Technologies (Schaumburg, Ill.; www.convergint.com). “However, after 9/11 it became recognized that some of the chemicals stored and processed could be stolen, sold on the black market and/or used as dirty bombs elsewhere or that someone could enter a facility and turn valves, releasing toxic or explosive chemicals, endangering employees and surrounding communities. Today, the goal of physical security is to keep the bad apples out of the facility and away from the chemical supply chain,” says Dillon.

“Gaining physical access to a chemical process ends the game when it comes to risk, since physical access is meant to be the last line of defense,” says Schneider Electric’s Abdallah. “The biggest threats from a physical perspective at these facilities are from natural disasters, terrorism and physical damage caused from loss of control (caused by a cyber or other breach). Due to the high degree of risk at chemical processing facilities, security must always be a high priority.”

He adds that cyberthreats that affect process control and safety could have a huge impact and must share elevated attention, adding another dimension to plant security.

Seth Carpenter, cybersecurity technologist with Honeywell Process Solutions agrees that loss of safety and process control are the two biggest cyberthreats for chemical processors. “Hackers getting into a system and taking actions that could compromise the safety of the plant, personnel or surrounding communities and gaining access in a way that could negatively impact production and availability of the facility are real issues for today’s chemical industry.”

The reason these threats exist, says Joshua Newton, security architect and team lead within the Connected Services Organization at Rockwell Automation (Milwaukee, Wis.; www.rockwellautomation.com), is because during the last five to ten years, the manufacturing and process world started to move quickly toward technology enhancements because they offered better analytics and big data and all the related production benefits. “So there was a push to become a connected enterprise,” he says. “However, it brought with it an inherent risk of exposure to devices.”

Neil Peterson, DeltaV product marketing director, with Emerson Automation Solutions (Round Rock, Tex.; www.emerson.com) agrees: “As we went to widely networked solutions with a lot of open communications and standards, it allowed the operating and financial benefits of communications between control and business systems, but also the stage was set for bad things to happen. It is now very possible for a hacker or cyber terrorist to get into a plant network and create havoc,” he warns.

What type of havoc? Malware attacks, which are often introduced via social engineering (for example, corrupt links sent via email) or unwittingly through portable hard drives, gain access and move laterally through a system gaining credentials, elevating privilege to an administrator and then moving about the system installing software and creating denial of service. “This means it is possible — if the right protections aren’t in place — for every workstation on a control system to be taken offline, leaving operators blind to the process,” explains Peterson. “Not only is this a dangerous situation, but it’s a costly one because you are forced to take the system down unless you are willing to run blind, so you’re losing production.”

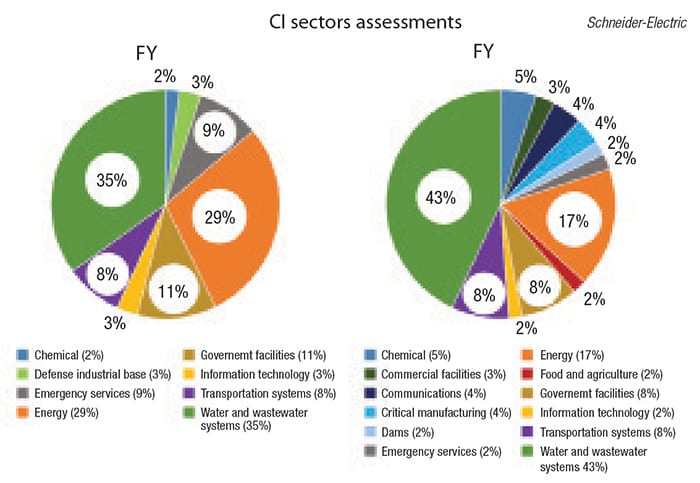

And these types of attacks are on the rise for many industries, including energy, critical manufacturing and infrastructure. According to Schneider Electric’s Abdallah, in 2015, the transportation industry reported 23 attacks and the water industry reported 25. In 2016, the energy industry reported 59 attacks, while critical manufacturing faced 63. Thus far in 2017, 2,000 food-and-beverage industry companies fell prey to a well-known ransomware attack called Petya.

Clearly attackers are getting more savvy and “those looking for the biggest bang for their effort may consider chemical facilities to be of higher value,” says Abdallah (Figure 1).

Figure 1. This diagram of the Critical Infrastructure Sectors Assessment for 2015 and 2016, as seen in the Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team (ICS-CERT) annual assessment report, shows that the number of assessments on chemical facilities has grown from 2% in 2015 to 5% in 2016 so there is recognition of the increasing threat

Attacks such as these are often indirect attacks in that the malware, once introduced, moves around the system on its own. There are also directed attacks where malware or ransomware gets into the system via an attachment or portable hard drive, corrupts a workstation and then “phones home to the attacker,” says Peterson. “From that point, the attacker starts issuing commands on the workstation using the user’s credentials and begins to pivot and roam around the network to find a target. If that target is the control system, the attacker then attempts to capture the credentials of the engineer responsible for that workstation and can remotely access the control system, making it do whatever he wants.”

Physical security solutions

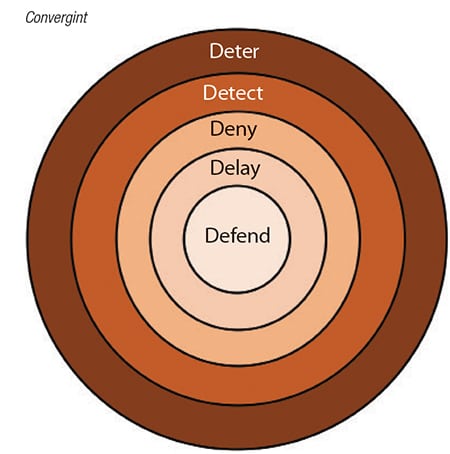

The good news is that most processors are taking steps to protect both the physical and cybersecurity of their facilities. “When it comes to providing physical security, most facilities are already doing a good job of it with fences, cameras and access control, but they should also be trying to stay one step ahead of the bad guys and one of the current areas of focus is in early detection,” says Convergint’s Dillon. “We want to give them earlier warnings if there’s a threat. We can put systems in place that let the bad folks know we see them and encourage them to move along” (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The goal of physical security is to keep the facility and chemical supply chain safe. Security should aim to first deter, then detect, deny, delay and, finally, defend. One of the current areas of focus is in early detection

Early detection systems include a variety of cameras and analytics, perimeter intrusion detection, ground-based radar and other technologies that allow security to see potential intruders before they get to the gate, so security has ample time to react when and if they do reach the gate.

“There’s a formula that can be used to create an appropriate early detection zone,” says Axis’s Morgan. “Using the formula, processors determine how many minutes it would take to stop someone from reaching the critical aspect inside the plant and, based on that time, they can figure out how far away, in distance, they need to detect someone approaching the plant.” And, at that distance point, they need to install early detection methods. Thermal cameras are one of the newer technologies for early detection, he says, because thermal technology offers improved analytics that examine pixel changes using advanced algorithms. “Thermal imaging has the ability to detect and analyze pixel changes and determine if they have the formality of a human being, and if those cameras are integrated with a video management system, security can be alerted so early action can be initiated,” says Morgan (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Thermal network cameras outperform a visual camera in dark scenes and can detect people and objects in 24/7 surveillance, from pitch dark areas to a sunlit parking lot. Axis thermal network cameras create images based on the heat that always radiates from any object, vehicle or person

Axis Communications

Integration of such systems, along with the use of mobile devices and apps, is another way processors are hardening the physical security of their facilities, says Bill Lorber, vice president of sales and marketing, with Apollo Security (Newport Beach, Calif.; www.apollo-security.com). “It is very easy to tie access control and video systems together so that security people can see when someone comes in and ensure the card matches the live image. In addition you can integrate systems so that when a door opens or there’s motion in an area, live video automatically appears on the security system monitor” (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Integration of physical security systems, along with the use of mobile devices and apps, is another way processors are hardening the security of their facilities Apollo Security

He continues: “Mobile devices are becoming much more important in this system as well, because you are no longer restricted to a guard sitting in a room with a monitor. The manager of security can also see activities when a group of people comes in or access video associated with events from a remote location via a mobile device using a live web version or app.”

This type of integration and automation allows security to evaluate a situation in milliseconds versus having an alarm event followed by several minutes of locating the correct camera for that location, then searching for a binder with instructions on how to respond and react, says Dillon. “Integration and automation provide a faster, more efficient response, which minimizes the cost of security, wasted time and potential for errors.”

Shoring up cybersecurity

The first layer in creating a system that’s hardened against a cyberattack, says Tony Downes, Global HSE Advisor with Honeywell Process Solutions, is in the system design. “There are things we can incorporate physically at the plant level that make it more difficult for someone to interfere with the process. For instance, because it’s a safety issue before it’s a security issue, we don’t have valves without backup systems, which helps prevent someone from opening a valve and causing a release,” he says. “There’s things we do for process safety reasons inside the plant design that make it inherently safer and, if those are in place, you can then get into defending the control system, making it even more difficult for a malicious attacker to do a lot of harm.”

Some of the simplest methods of thwarting a cyberattack include what Rockwell Automation’s Newton calls “basic cyber hygiene,” such as keeping operating systems up to date with patches. “Even though cyberattacks seem very sophisticated, under most circumstances, the methods employed are known attack vectors that can be prevented with patches and updates.”

Beyond installing patches, control system providers suggest a layered approach to cybersecurity. “Defense in depth is the best approach and not just because we can provide each layer, but because it is the most comprehensive protection. Beyond that, always make sure the cybersecurity you’re putting in place is context based. What you’re trying to protect is your process, so the first layer of defense is making sure that if your control systems are exposed to external connections, that they are limited, read-only and always monitored,” says Alexandre Peixoto, DeltaV cybersecurity marketing manager with Emerson Automation Solutions. He adds that applications should be run on an embedded system, which is harder to compromise. Further, processors should use firewalls, which allow a certain flow of communications to devices, but prevent others that aren’t approved. Antivirus software should be employed at workstations to prevent known threats from infecting them. And on top of this, we are starting to see whitelisting applications, which prevent software that has not been approved from running on the system.”

However, while all this helps prevent attacks, control system providers say that defense is not enough, so monitoring has become more popular as the threat grows larger. “Cybersecurity is not just about protection,” says Peixoto. “Monitoring helps the user detect anomalies by monitoring data across different networks to make sure everything moves the way it should. Control systems tend to work on a predictable schedule, so when you see an anomaly, it is easy to detect.”

But, because chemical processors often prefer to focus on making chemicals, not defending against cyberattacks, some control system vendors are offering managed services. “They can hire people to help out with anything from assessing their systems and determining where they stand in the defense against cyber attack and what steps they still need to take, as well as recommending and installing necessary technologies and then keeping up with patches and updates for them,” says Honeywell’s Carpenter (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Since chemical processors prefer to focus on making chemicals, not defending against cyberattacks, control system vendors, such as Honeywell, offer managed services, which assist customers with services such as assessing their systems and determining where they stand in the defense against cyberattack, what steps they still need to take, as well as recommending and installing necessary technologies and keeping up with patches and updates

Honeywell Process Solutions

And, there’s certainly no shame in taking help from experienced security professionals as there is a lot to keep up with in an effort to keep facilities properly locked down and safe from harm. “What’s most important is taking the steps to protect against all forms of attack because chemical facilities are attractive to potential terrorists,” says Honeywell’s Downes.