Drinking water can be contaminated with micropollutants, including steroid hormones that are used as medical substances and contraceptives. Although their concentration in wastewater may be only a few nanograms per liter, this small amount can already damage human health and adversely affect the environment. Due to the low concentration and small size of the molecules, steroid hormones not only are difficult to detect, but also difficult to remove — conventional sewage-treatment technologies are not sufficient.

To handle this problem, professor Andrea Iris Schäfer, head of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology’s (KIT; Germany; www.kit.edu) Institute for Advanced Membrane Technology (IAMT) and her team have developed a process that combines ultrafiltration (UF) with activated carbon adsorption in a single filtration medium.

IAMT researchers have further developed and improved this process together with filter manufacturer Blücher GmbH (Erkrath, Germany; www.bluecher.com), while colleagues from KIT’s Institute of Functional Interfaces, Institute for Applied Materials, and the Karlsruhe Nano Micro Facility characterized the material. The study was published in the October 15 issue of Water Research.

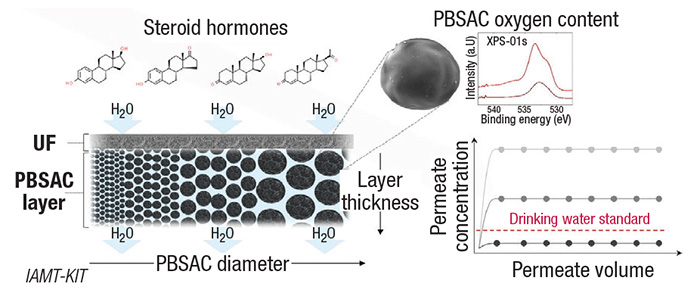

In the process (diagram), water is first pressed through a semipermeable membrane that eliminates larger impurities and microorganisms, Schäfer explains. “Then, water flows through the layer of carbon particles behind (the membrane), which bind the hormone molecules.”

Scientists used modified carbon particles (polymer-based spherical activated carbon; PBSAC). The key was to determine the optimal diameter of the carbon particles. Using an activated carbon layer of 2-mm thickness, the researchers decreased the particle diameter from 640 to 80µm and succeeded in eliminating 96% of the estradiol contained in the water. By increasing the oxygen concentration in the activated carbon, adsorption kinetics was further improved and a separation efficiency of estradiol of more than 99% was achieved. “The method allows for a high water flowrate at low pressure, is energy-efficient, and separates many molecules without producing any harmful byproducts,” says Schäfer. “Our technology allows us to reach the reference value of one nanogram estradiol [the physiologically most effective estrogen] per liter drinking water proposed by the European Commission.”