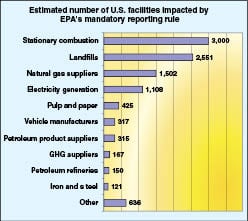

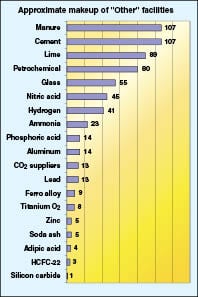

As 2009 came to a close, the U.S. crossed a key milestone in the path toward regulating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Nearly 10,000 facilities (Figures 1 and 2) — a significant portion of them in the chemical process industries (CPI) — became subject to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA; http://www.epa.gov; Washington D.C.) Final Mandatory Greenhouse Gases Reporting Rule. The rule requires that applicable facilities begin collecting data on January 1, 2010 for annual GHG emission reports that are due to EPA by March 31, 2011. Although the rule itself does not limit GHG emissions, the collected data will be used to inform future climate-change policies and programs, EPA says.

Whether it is because of the relatively quick pace that this rule took in being made official or the extremely loud noise from broader GHG debates in the mainstream media, many chemical engineers found themselves in a year-end rush to prepare for the January 1 milestone. Others have requested extensions, which will expire at the end of this month. Meanwhile, for all facilities that are subject to the rule, the next deadline for preparing a formal monitoring plan is right around the corner on April 1.

As the U.S. CPI grapple with the specifics of EPA’s reporting rule, curiosity is building globally around the extent to which GHG reduction initiatives will be in demand. For now, the future of U.S. climate policy is caught in a storm of political and social debates, clouding the picture at the regulatory level (for more, see this month’s Editor’s Page where we ask you to weigh in with your own opinions). Nevertheless, GHG regulation is already a reality in other parts of the world, and a clear motivation for GHG reductions is emerging through the U.S. financial sector. Recent moves to increase transparency into a given company’s GHG risks and opportunities financially could provide the ultimate incentive for the CPI’s investment into technologies that help reduce so-called carbon footprints. After all, financial motivation is primarily what has been behind most of the CPI’s GHG reductions thus far.

Key aspects of the rule

In general, EPA’s GHG reporting rule (http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/emissions/ghgrulemaking.html) defines applicability and requirements for stationary combustion sources, 20 chemical process categories, and more (see the box, p. 19). For most sources, the reporting threshold is 25,000 metric tons per year (m.t./yr) CO2 equivalent (CO2e). The gases that must be reported are CO2, CH4, N2O and fluorinated GHGs, which include HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons), PFCs (perfluorocarbons) and SF6 (sulfur hexafluoride). Each facility must evaluate which part (or parts) of the rule apply. For example, a large petroleum refinery with cogeneration could conceivably be subject to all three of the following subparts: stationary combustion, petroleum refining and petroleum product suppliers.

Within each subcategory, reporting requirements are divided into four tiers, which define whether the data should be calculated or measured by instrumentation and methods for doing so. “Tier 1 is the easiest to measure but the least accurate,” explains Terry Moore, principal at Carbon Shrinks LLC (Austin, Tex.; http://www.carbonshrinks.com), while “Tier 4 is the most complex and expensive to measure but the most accurate.” Since tiers are generally aligned according to the size of the unit, Moore says, a single facility could be directed to use different tiers for different combustion or industrial process units. Meanwhile, a facility may elect to use the methods of a higher tier than is applicable, but not a lower one.

Measurement methods apply not only to direct measurement of GHG emissions, says Moore, but to other data that must be reported for a given industrial process and to data that are required for the calculations. Necessary data can include fuel used, high heat value of fuels, organic carbon content of raw materials and so on. EPA will verify emissions data as opposed to involving third parties.

Areas of ambiguity

In assessing how to meet the requirements of the mandatory GHG reporting rule, chemical processors have encountered several areas of ambiguity. One of those areas involves the use of existing O2 monitors in calculating CO2 emissions. “This is allowed in California’s GHG rule, for example, but not allowed under the EPA rule,” says Barney Racine, software development manager at Honeywell Process Solutions’ (Phoenix; http://www.honeywell.com/ps) Environmental Solutions Group.

Another area of uncertainty is calibration. EPA says that flowmeters and other monitoring equipment need to be calibrated to meet 5% accuracy requirements prior to April 1, 2010. In a document entitled “Special Provisions for 2010” and issued in January, however, EPA qualified that requirement by saying that initial calibration may be postponed after April 1 in two cases. The first exception describes monitoring equipment that has already been calibrated according to a method specified in the applicable subpart of the rule and for which the previous calibration is still active. In this case, the instrument does not need to be recalibrated until the previous calibration has elapsed. The second exception is for units that operate continuously with infrequent outages and in which calibration would require removing the device from service, thereby disrupting process operation. In this case, initial calibration may be postponed until the next scheduled maintenance outage.

Recalibration, itself, has also come under question because the EPA rule refers to a minimum recalibration frequency while also alluding to the instrument manufacturer’s specification. “If the manufacturer’s frequency is different than EPA’s, the lesser of the two applies,” explains Allen Kugi, application engineer at Fluid Components International (San Marcos, Calif.; http://www.fluidcomponents.com).

Possibly the biggest issue or controversy, discussed recently at the National Petroleum Refiners’s Assn. (NPRA; Washington, D.C.; http://www.npra.org) GHG Conference in Houston, was a ruling that flowmeters had to be temperature-and-pressure compensated with instruments located at the flowmeter, rather than from other process areas, says Chris Jones, Green Initiative marketing leader at Honeywell Process Solutions. “This provides an enormous challenge for most companies, as they do not have temperature/pressure instrumentation at every flowmeter.” At the meeting, the EPA stated that it “heard the outcry” and would re-evaluate its decision, Racine says.

Timeline and the next steps

In every subpart that identifies specific measurement methods that require instrumentation, affected facilities must comply by installing or upgrading instrumentation if it doesn’t meet specifications. Timing on such upgrades differs for two cases, explains Carbon Shrinks’ Moore:

1. CEMS upgrades: Facilities required to use Tier 4 have until January 1, 2011 to get their continuous-emissions-monitoring-systems (CEMS) upgrades installed and certified

2. Other instrument upgrades: Facilities may use “best available measurement methods” in lieu of required instrumentation until March 31, 2010. After that date, they must either use the required instrumentation or receive an extension from EPA, but the final date to request extensions was January 31, 2010

Beyond that, the next major deadline is for completion of a monitoring plan, which is required to be in place at each reporting facility by April 1. Since the purpose of the monitoring plan is to document the process and procedures for collecting and reviewing the data needed to estimate annual GHG emissions, EPA says, the plan needs to be in place prior to collecting data to ensure consistency and accuracy. EPA further emphasizes that the plan does not have to be complex and can rely on existing corporate documents like standard operating procedures (SOPs) and monitoring plans developed for compliance with other air programs. Even facilities that have been granted an extension to use best available methods to estimate GHG emissions for a period beyond April 1, 2010, are required to have a plan developed for the basic procedures that will be used to collect data. As a facility’s data collection methods change and evolve, the monitoring plan must be revised to reflect the changes.

EPA says it intends to have the electronic reporting system operational in January 2011, approximately three months in advance of the March 31, 2011, reporting deadline. EPA intends to make training on the emissions reporting system available in fall 2010 and continuing into 2011. The electronic reporting system will include a separate module for registering users and facilities, scheduled to be operational and ready for training by summer 2010.

What is covered?The U.S. EPA’s Mandatory Greenhouse Gas Reporting Rule is divided into 25 source categories and 5 types of suppliers of fuel and industrial GHGs. It is important to recognize that any facility can be subject to multiple source categories. “All-in” source categories Suppliers * Processes that are not co-located with a HCFC-22 production facility and that destroy more than 2.14 metric tons of HFC-23 per year |

Collateral impact

Even though the expressed intent of EPA’s GHG reporting rule is to inform public policy, the results could very easily have broader implications. “If EPA publishes, say, industry-average GHG-intensity numbers for pulp-and-paper facilities of x m.t. CO2e per ton of paper manufactured, some big paper customers may use that to set a procurement policy of y m.t. CO2e per ton of paper as their minimum standard,” says Carbon Shrinks’ Moore. “In general this would reward more efficient plants and penalize less efficient ones, as well as create a new type of business case for investment in reducing GHG emissions for future annual reports to the EPA.”

Already, one new index aims to achieve a similar result sooner. Last month, ECPI, a Milan-based research, ratings and indices company, announced the launch of its Global Carbon Equity Index. Developed in partnership with Arthur D. Little, a global management consulting firm, the new index aims to highlight 40 companies best equipped to prosper in a tougher climate-legislation environment. “The ECPI Global Carbon Equity Index has proven to outperform the market in both bull and bear markets, even through one of the worst recessions in history,” says Paolo Sardi, CEO of ECPI Luxembourg. “Regular outperformance will not only provide investors with financial security but help dispel the myth that sustainable investment issues are only a concern for investors in strong, non-turbulent market conditions.” Carbon-intensive sectors will be selected annually based on available carbon emissions data. Akzo Nobel BV, Johnson & Johnson, Eni S.p.A. and VALE SA are some of the top performers from the CPI that make up the index this year.

Over the next year, as the U.S. CPI begin to collect GHG emissions data, the connection between carbon intensity and financial performance will become more visible for any company that is publicly traded in the U.S. On January 27th, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued new interpretive guidance on existing SEC requirements to clarify what publicly traded companies need to disclose to investors in terms of climate-related “material” effects on business operations. The guidance specifically highlights impact of legislation and regulation; impact of international accords; indirect consequences of regulation or business trends; and physical impacts of climate change.

Increased investor scrutiny and any prospect of GHG regulations would influence how the CPI approach GHG reporting in the future. For now, most reporters “are adopting a wait-and-see attitude, and just meeting the minimum reporting requirements,” says Honeywell’s Racine. In the future, however, reporters that are currently allowed to estimate emissions using default factors from the rule might be motivated to install instrumentation to more accurately reflect their lower emissions, says Carbon Shrinks’ Moore.

If that is not enough, process improvements and, potentially, carbon capture and storage (CCS) would be required. While CCS is not yet proven commercially, its implementation has fewer obstacles in the CPI than it does in power generation applications. “One of the nice things about the CPI is that the carbon dioxide is fairly pure,” explains Mike Arne, assistant director at SRI Consulting (Menlo Park, Calif.; http://www.sriconsulting.com). “There is a tremendous amount of energy that goes into scrubbing the CO2 from coal power plants. Compressing it and putting it into the ground requires energy, too, but not as much.”

Rebekkah Marshall