Development of robust preparation and response procedures can help chemical plants to weather disaster events and return to normal operations in a safe and efficient manner

Having a well-defined and understood approach to disaster preparation and response will ensure that companies and facilities are in a good position to manage a disaster event as it occurs, and drive recovery and restart once the event concludes (Figure 1). Coordination of several wide-ranging departments, including, for example, operations, procurement, emergency response, communications and public affairs and business planning, will allow for rapid deployment of the necessary resources to limit damage and manage business interruption of affected facilities and the supply chain. Planning, training, communication, exercising the prevention and response plan and critique of activities are elements of the overall preparedness plan that should be reviewed and tested frequently to evaluate the proficiency of key participants. This article intends to describe the importance and components of disaster preparedness processes, procedures and training to ensure effective preparation for, and response to, manmade or natural disaster scenarios.

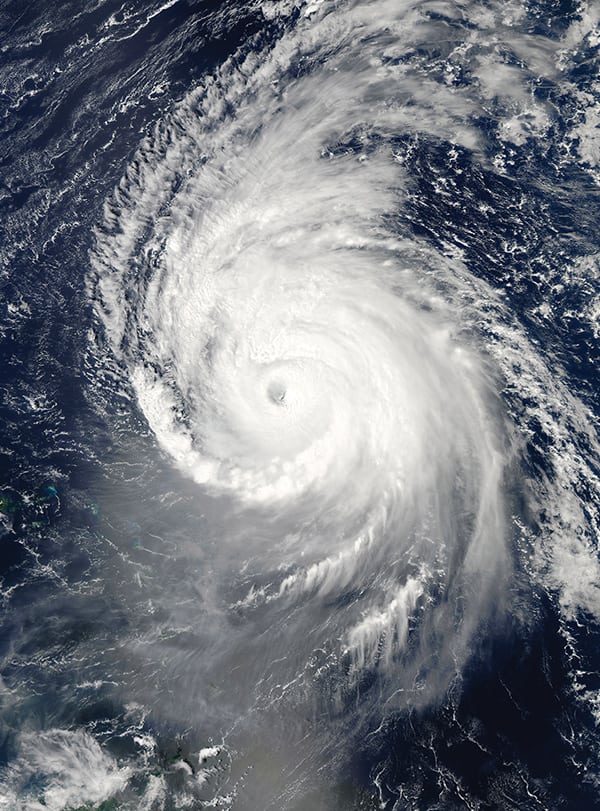

FIGURE 1. Disasters — both natural and manmade — can create uniquely dangerous conditions for chemical plant personnel and surrounding communities, but there are many measures that can be taken to prepare for and diminish the potential damage caused by such events

Disasters come in many forms and may include natural disasters, such as hurricanes, earthquakes, tornadoes, flooding and wildfires, and human-made disasters, such as industrial accidents, transportation events and chemical, biological and radiological events. The type of disaster event your organization should plan for may depend on geographical location, type of manufacturing process (for example, chemical, radioactive and so on) or proximity to other industrial organizations.

Whether you call it disaster preparedness, emergency response planning, crisis management or something similar doesn’t much matter, but the elements do. Missing a piece of the pie in this area can make a huge difference in how an event plays out. Each facility’s overall crisis or emergency response plan should include the elements discussed in the following sections, at a minimum. Note that this is not an exhaustive list, but a guide — individual companies should assess specific elements for applicability.

Risk assessment

Assessing risk is the first step in disaster preparation and should not be taken lightly. This is your company’s opportunity to evaluate the potential for a disaster event and determine what your exposure might be. For example, if you have facilities in the U.S. Gulf Coast, a primary natural risk is threat of hurricanes (Figure 2). For those on the U.S. West Coast, earthquakes and wildfires are a primary concern. All manufacturing facilities need to assess the risks associated with their processes (for instance, chemical release, fire or explosion), and what offsite consequences might occur.

FIGURE 2. In order to best facilitate preparedness for natural disasters like hurricanes, chemical manufacturers must be vigilant about assessing their site’s risks by closely following regional weather patterns, as well as evaluating site-specific chemical-processing risks

Risk assessments should include the following:

- Risk of exposure to natural disasters (such as hurricanes, tornadoes or earthquakes)

- Risk for internal process upset events (fires, explosions, releases and so on)

- Risks from business or supply-chain interruption

- Other risks as determined by site operation or location

Once the risks are determined, controls either already in place or needed to prevent or minimize the event should be listed. When the controls are determined to be inadequate or unavailable, a plan should be created to reduce or eliminate the risk. The assessment should be reviewed on a specifically determined frequency (at least annually) to ensure that existing controls are effective and that planned controls are moving forward. Knowing what risks your site may be exposed to will help determine what preparation and response planning is necessary. This knowledge serves as the framework for your site’s emergency response plan (ERP).

Emergency action and response

The backbone of your preparedness plan is the facility’s ERP. An ERP is designed to provide the user with guidelines for managing the various types of emergency and disaster situations, such as fire, chemical release, power outage, severe weather, security threat or even an emergency at a neighboring facility. This document can be a standalone procedure or policy, or may be a compilation of related procedures that address specific elements of emergency management.

The ERP should be designed to meet both regulatory and company requirements and be readily available to all site personnel. Posting an electronic version on a company website is recommended so that access is available from almost anywhere. However, keeping a hard copy in a specified location, such as a designated emergency operations center (EOC), is necessary, especially in the event of a power-loss event.

Elements of an ERP may include the following core plan components, which provide direction for responding to incidents regardless of nature or severity:

- Discovery: Actions to be taken by personnel upon notification of potential threat (such as severe weather) or upon discovery of an event (such as a fire or spill) and initial control measures

- Response: Procedures for internal and external notification, establishing incident command, preliminary event assessment, establishing response objectives, implementing response actions and mobilizing resources

- Sustained actions: Measures to transition from emergency action to continued mitigation or remedial action

- Termination and follow-up activities: Procedures for terminating the emergency activities, demobilizing response resources and performing incident investigation and critique activities

The core components demonstrate the overall intent of the ERP and will be supplemented by activity-specific procedures, essentially the “how-to” for each section. Examples include procedures for reporting emergencies, severe weather response, employee notification, incident command structure and EOC, accountability of personnel and shelter-in-place or evacuation, just to name a few.

Training and drills

To feel confident that your planning will translate into effective execution when an event arises, it must be well understood by team members and practiced with some frequency. Training of team members is paramount to success and should be conducted for any personnel with specific responsibilities, and general training is recommended for all personnel in the base elements of the plan and where the plan is located. Training may include the following:

- Initial review of emergency response plans and roles

- Training on specific leadership roles and responsibilities, such as incident coordinator, communications coordinator and other roles listed in the plan

- Training for site event-management personnel, such as the onsite incident commander and emergency response team personnel, as well as general team-member training for emergency event notification, communication, evacuation and so on

Once personnel are trained and familiar with plan elements, drills should be conducted frequently to verify that personnel understand the training provided and that the plans are effective. It is recommended that a drill schedule be established and become an integral part of the disaster preparation process. Site leadership should be engaged and should drive participation throughout the organization. Drill scenarios should be based on events likely to occur (established in your assessment), and be designed to:

- Test the response capability and effectiveness of the organization

- Determine gaps in planning, training or communications

- Find opportunities for improvement

Drills vary in size and complexity, from straightforward tabletop exercises in an EOC room up to multi-site or regional disaster drills involving mutual aid entities, external specialty resources and government agencies. The type or size of drill conducted should be based upon the potential extent of an event and the maturity and capability of your organization.

Critique. Anytime a drill is conducted or an actual event occurs, an event critique should be completed. The critique is a formal review of the event and looks at all elements of the response, from the initial report of an event up to and including restoration of operations. The critique will help assess what went well and what has opportunity for improvement. Actions (and action plans) created from the critique should be logged, assigned to responsible personnel and tracked to completion. Agreed-upon actions should be completed in as short an amount of time as practicable so that improvements are in place ahead of a new event.

Experiences during Hurricane Harvey

While writing this article, the Gulf Coast was hit by Hurricane Harvey and the authors’ company’s planning, training, procedures and resources were put to the test, as it has three manufacturing facilities in the affected area.

As Tropical Storm Harvey was initially moving through the Caribbean, the three facilities in the Houston area took note and began preparations for the potential hurricane according to site-specific hurricane response plans, including staffing plans, supply and equipment staging, securing the facilities and establishing an offsite hurricane EOC. Communications between the sites and the corporate office were initiated regarding response planning and status, and when it became clear that the storm had reached hurricane status and was targeting the greater Houston area, company industrial leadership convened the crisis management team (CMT) to assist with planning, response and recovery efforts for the affected facilities and team members.

The CMT is a business-unit function, and serves to provide a strategic approach and implementation measures to assist facilities in mitigation of crisis events. These events can be a natural disaster, facility emergency event (such as fire or explosion), business or supply-chain interruption, or any other event that could have a negative impact to the company. The crisis management plan works in concert with site-level emergency action plans to ensure the most positive outcome is achieved.

Upon activation of the CMT, the facilities in Houston now had the support of the corporate office and all associated resources. While facilities were busy executing site-level actions, such as staffing planning and securing the process, the CMT was busy looking at business interruption potential, logistical concerns and ensuring that team members in the area would have the supplies and continued support needed during and after the hurricane.

As the hurricane event progressed and severe flooding occurred in the area, it was evident that team members would likely be evacuated from their homes and that many would see damage and property loss. Throughout the event, the hurricane EOC and the CMT worked to maintain accountability of all team members, onsite and offsite, and offered assistance as needed to ensure their safety. This included temporary lodging, generators, tree removal and other supplies.

By working together, the hurricane EOC and the CMT were able to manage customer and supplier disruption potential, plan for safe restart of affected facilities and, most importantly, assist team members with much-needed supplies and lodging. This was all possible due to execution of existing procedures and policies that were well understood, well maintained and exercised through thorough drills.

Procedures

Site procedures should be developed to manage preparation and response activities during severe weather. In the following examples, hurricane preparedness is used. Site procedures should include specific actions to be taken prior to arrival of the storm, response actions during the storm and actions in the recovery period once the storm has passed.

Key elements of a hurricane preparation procedure are described in the following paragraphs.

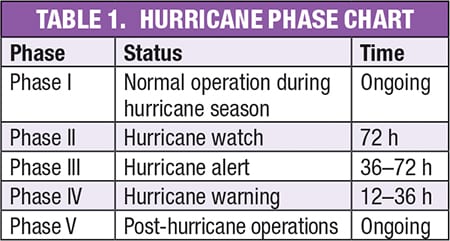

Process for determining event phases and associated actions. This phase chart guides the site to initiate prescribed actions, such as securing the facility, ordering or staging supplies, developing staffing plans and evaluating logistical and business interruption concerns. Table 1 is an example of a hurricane phase chart.

Process for selection and management of a “Hurricane Crew.” This team is responsible for site preparation and executing requirements of the procedure. This may also be the team designated to staff the facility during the weather event.

Weather information. Select a service that provides daily weather notifications and ensure the site has NOAA weather-band radios available.

List of equipment and supplies. The list includes the necessary supplies to support activities on site during a weather event. This may include food, radios, fuel, batteries and generators.

Communication process and tool. This tool provides the ability to provide emergency or general information and instruction to affected personnel. Service should be able to reach multiple formats, including home or mobile phones and email. The process should account for personnel both on- and offsite.

Communication with customers, vendors and suppliers. Since the site will likely not be manufacturing or shipping product temporarily, contact with customers, suppliers and vendors should be made so that needs are clear and action plans are in place. Depending on the company’s structure, this activity may be executed by the supply-chain business unit or by the corporate office.

Need for and activation of offsite hurricane EOC. This location should be established outside of the expected hurricane area in a location easily accessible by facility personnel. A hotel’s meeting or ballroom is a good location.

Communication and integration with crisis management. A process should be established for communication with corporate or home-office leadership. Where company structure allows, a business group may assist with managing resources and response efforts from a central location, soliciting support from other corporate functions.

Process for determining shutdown or evacuation of the site and community. This element addresses the decision process for site or local community evacuation or mandatory evacuation, and will depend on the severity of the weather event. The process should take into account site and regional evacuation orders.

Process for emergency supplies for personnel. The weather event will impact site employees and their families. A plan should be in place to address support for their needs outside of the business. Elements may include lodging, fuel, generators, tree removal and so on.

Process for returning to the site once the event has passed. This should include the process for communicating to site personnel and stakeholders, as well as employing an advance team to assess potential damage and restart capability.

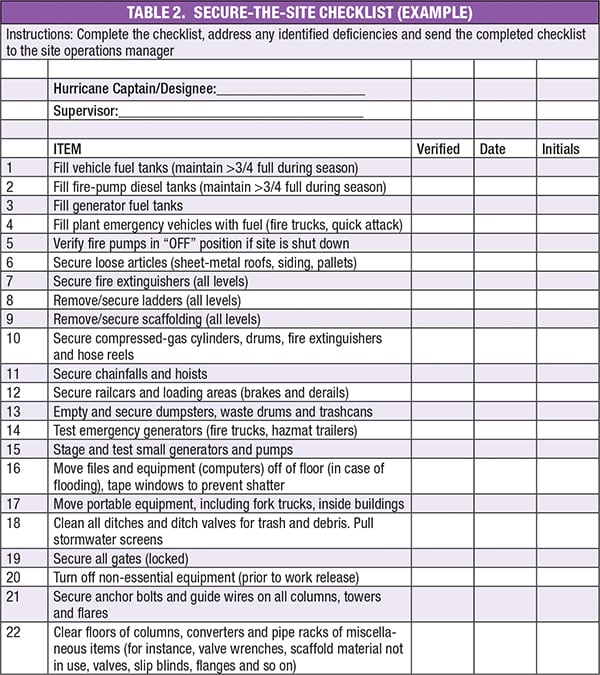

When it is clear that severe weather will affect the facility, site personnel should initiate procedures to secure the site, including removing objects that could become projectiles in high winds, moving equipment from potential flood areas and powering down non-essential equipment. Table 2 is an example of a secure-the-site checklist.

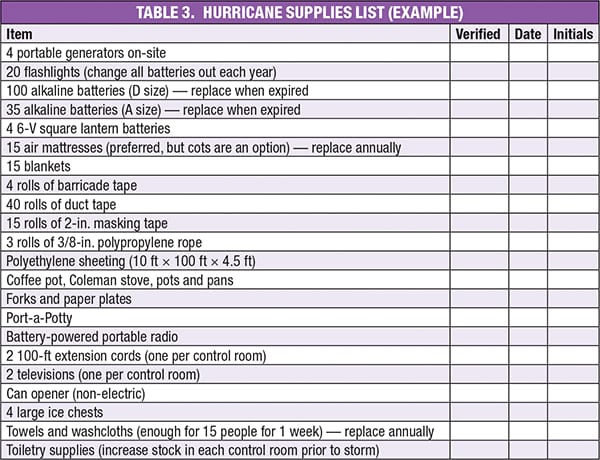

In addition, supplies necessary for the site during the event should be readily available and inventoried. A check of availability and accessibility of supplies should be conducted a few times throughout the year to ensure supplies and equipment are available and in good working order. Table 3 is an example of a hurricane supplies list.

When the weather event concludes, there may still be a lot of work to do. Personnel may be unable to return to the site, and many supplies may be needed. Logistical efforts may be more challenging at this point. Having a strong site-response plan backed by support from a central or corporate organization will drive a faster recovery effort both in the community and on site.

While hurricane preparation was used as an example in this article, the same basic approach exists for other severe weather events or natural disasters, such as tornadoes or earthquakes. Assessing risk, pre-planning, procedure development, established roles and responsibilities and regular evaluation of the response plans through drills and exercises will better prepare organizations to manage a disaster event and limit impact to the facility and surrounding community.

Edited by Mary Page Bailey

Authors

Thomas E. Cubler, Jr. is a subject matter expert (SME) in the area of health and safety at Braskem America (750 W. 10th St., Marcus Hook, PA 19061; Email: tom.cublerjr@braskem.com). His work involves administration of health, safety and incident management programs, including security and emergency response programs, industrial hygiene assessments, incident investigation and training. Cubler has more than 20 years of experience in industrial health and safety. Before joining Braskem, he was Health, Safety & Security manager for Honeywell. Also, he previously held positions with Sunoco and Ciba Specialty Chemicals. Cubler holds a B.S. in occupational safety and hygiene management from Millersville University of Pennsylvania, and is a Certified Safety Professional and a member of the American Society of Safety Engineers.

Tim Thompson is a member of the corporate health, environment and safety (HES) team at Braskem America (6021 Fairmont Pkwy, Pasadena, TX 77505; Email: tim.thompson@braskem.com). With more than 30 years of HES leadership and technical experience, Thompson’s primary focus is safety and health. He has served as a subject matter expert for crisis and emergency response, and has coordinated several disaster operations, including during Hurricane Ike in 2008. He holds a B.S. in safety science from Indiana University of Pennsylvania and is a Certified Safety Professional.

Rey Rosas is the leader of the business HES team at Braskem America (6021 Fairmont Pkwy, Pasadena, TX 77505; Email: reynaldo.rosas@braskem.com). His work involves providing the functional support resources, industry best practices and HES improvement tools to Braskem America’s five manufacturing facilities and tech center in the U.S. Rosas has 29 years of accumulated manufacturing and maintenance experience, including 5 years as the Braskem America Seadrift operations facility manager. During Hurricane Harvey, Rosas led the remote EOC from Austin, Tex. He holds a B.S.Ch.E. from Texas A&I University, Kingsville, Tex.