Demand for refined products has dropped sharply, challenging petroleum refineries with compressed margins, but a deal was struck on global production cuts

The large-scale shutdown of economic activity related to the global pandemic response has caused demand for refined petroleum products to plunge dramatically, placing refiners around the world into a difficult situation. Refinery production cuts are common, while some plants have been idled.

“In countries where stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures have been issued, gasoline demand is down by 50% and aviation fuel demand is down 70% or more,” says Steve Sawyer, director of refining for Facts Global Energy (FGE; London, U.K.; www.fgenergy.com). “Diesel demand has kept up a little better because trucking deliveries are still being made, but despite that, diesel has fallen by 30% at least.” Sawyer adds “Really, demand for all hydrocarbons coming out of a refinery are down.”

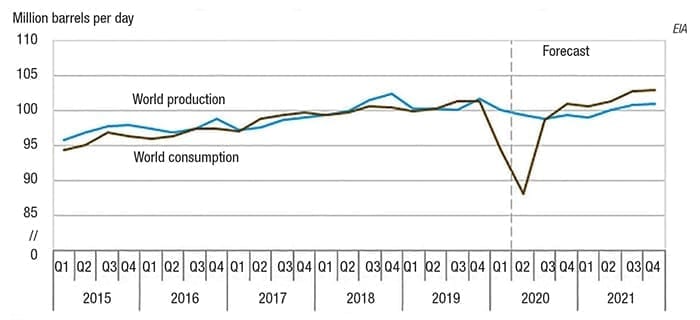

Sawyer says April demand for refined products could be 23 million barrels per day (bbl/d) lower than the corresponding value from April of last year. “May could maybe be a bit better, but if you’re in a deep hole, and you take one step up, you are still in a deep hole.” Weak demand will persist into June, and what happens after that depends in large part on what happens with the public health crisis, he says.

Deal struck on production

The sharp decline in the demand for refined products coincided with oversupply of crude oil that was precipitated by disagreements between Saudi Arabia and Russia in March over reductions in crude production. In April, a largely unprecedented coordinated effort to stabilize global crude oil prices took shape, as Russia, Saudi Arabia and the other nations of the so-called “OPEC-Plus” group (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries; www.opec.org, plus allies) finalized a deal on cuts to oil production on April 12.

During a virtual meeting of the OPEC-Plus oil ministers, the group agreed to a reduction in oil production of 9.7 million bbl/d from May 1 to June 30, and called on other oil producers to contribute to the effort. The OPEC-Plus agreement says the cuts will taper to a 7.7 million bbl/d reduction from July to December 2020, and a 5.8 million bbl/d reduction in 2021.

The U.S. also became involved, with President Trump pushing Saudi and Russian leaders for a deal on production cuts and stepping in to help Mexico meet its production cuts. U.S. Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette announced April 10 that the U.S. would open its Strategic Petroleum Reserve to store as much oil as possible. “This will take surplus oil off the market at a time when commercial storage is filling up and the market is oversupplied.”

Despite the agreement, downward pressure on oil prices was expected to continue, and crude oil storage facilities are forecast to be stretched. Following the announcement, WoodMackenzie (Edinburgh, U.K.; www.woodmac.com) vice president for macro oils Ann-Louise Hittle said the agreed-upon reduction would support crude oil prices over the second quarter. However, while the announced cuts will offer some degree of relief to the oil industry, they are insufficient to match the demand destruction that has been observed because of the pandemic-related shutdowns, she says.

Further, FGE’s Sawyer says there are questions surrounding how the agreement will be implemented in practice, including those of compliance, and inventory levels. Ultimately, all oil market projections beyond the next couple of months depend on the trajectory of global oil demand, which remains at the mercy of COVID-19, FGE says.

As of press time, crude prices remained depressed, with West Texas Intermediate futures trading at $18.27/bbl, for example, and crude inventories rising, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA).

‘Double whammy’

The supply and demand picture for crude oil products creates a difficult period for refineries. “Most of the time, economic theory states that when prices for a resource go down, we will use more of it. But now, with demand for refined products also dropped because there’s less driving and less aviation, we have the unusual situation of low oil prices coinciding with low demand for refined products,” comments Arij von Berkel, research director at Lux Research Inc. (New York, N.Y.; www.luxresearchinc.com).

The demand destruction due to the virus, combined with the drop in crude prices was a “double whammy” for refiners, says Sawyer.

“In the current situation, you could produce refined products at a low price, but no one is buying,” von Berkel says. “Many refineries are reducing production, or looking to store products in the hopes of selling it later. Refineries may also try to change the product mix, possibly making less aviation fuel and more shipping fuel right now, for example,” von Berkel says.

Pandemic response

The response from the refining industry to the pandemic is ongoing, and thus far, it has been multi-dimensional, with operations- and production-related responses accompanied by employee public health measures and humanitarian efforts.

FGE’s Sawyer predicts that refinery run cuts related to the COVID-19 shutdowns are going to be at least 15 million bbl/d globally, year over year in April and May. “Some refineries are going to shut as a result of that, temporarily,” he says. Examples of refinery shutdowns have been observed in the U.S., Canada, Italy, South Africa and elsewhere. Unfortunately, some of the refineries that have been forced to close because of COVID-19 may struggle to restream, he says.

“We may see shutdowns of fluid catalytic cracker (FCC) units if gasoline demand stays low,” Sawyer says. “We have seen some examples of that as well.” Some refineries that are in turnaround may not restart for a few months.

In the U.S., ExxonMobil Corp. (Irving, Tex.; www.exxonmobil.com) is among many companies with refining operations that have cut production. ExxonMobil cut production at its 502,500-bbl/d Baton Rouge, La. refinery, as low demand has increased inventories and filled storage tanks, the company says. ExxonMobil has also cut contract workers at the site by 1,800 people in April. At least three refineries in California have cut production, as well.

Marathon Petroleum Corp. (Findlay, Ohio; www.marathonpetroleum.com) idled its Gallup Refinery and related assets in Jamestown, N.M. beginning on April 15. Marathon spokesperson Jamal Kheiry says the company does not expect any supply disruptions in the region because it can meet customer commitments with other assets in its network.

“Our intent is to maintain regular employee staffing levels during this temporary idling period, with employees assigned to tasks that are necessary to support our idle status and eventual return to normal operations. At this time, the duration of the idling period is unknown; however, it is our intent to return to normal operations as soon as demand levels justify doing so,” Kheiry says. The company would not comment on specific crude acquisitions and refinery runs.

Marathon also provides an example of how large refining companies are handling their personnel during the public health crisis. To reduce the probability of spreading COVID-19 from otherwise healthy people to those most at risk, Marathon has reduced facility staffing to only essential personnel and implemented remote working programs wherever feasible, the company says, adding “This is in addition to a variety of other mitigation efforts, including social-distancing, travel restrictions, self-quarantine guidelines, enhanced cleaning protocols, and more.”

On the humanitarian side, many refining companies are finding ways to give back to their local communities. For example, Valero Energy Corp. (San Antonio, Tex.; www.valero.com) Foundation committed $1.8 million in late March to support organizations on the front lines of the COVID-19 treatment and public health response. In addition, Valero is also providing gas cards to selected charitable organizations to provide access to essential fuels and products for their operations. Meanwhile, Marathon donated 575,000 N95 respirator masks to healthcare facilities in 20 states where the company has operations, and through the Marathon Petroleum Foundation, donated $1 million to American Red Cross Disaster Relief.

Preview of the future?

The current demand falloff due to the COVID-19 response is occurring within a larger context of broader demand shifts, and some industry experts are drawing connections between the current situation and what the future might look like 15–20 years from now. Most predictions put the peak global demand for gasoline around 2035, after which demand will decline as a consequence of the automotive fleet changing to electric power or hydrogen, and more efficient internal combustion engines.

“Everyone expects a drop in demand after 2035, which will also be accompanied by a drop in price, so the current situation is almost a rehearsal for 15 years from now,” says Lux Research’s von Berkel. “It’s like a stress test for oil companies. If you want to know how prepared they are for peak demand, have a look at the present.”

Following the “standard playbook” response of cutting costs, von Berkel says, “the question then becomes where do you cut costs and where do you stop investing?”

Crude-to-chemicals

While demand for ground transportation fuels will likely decline in coming years, demand for petrochemicals is still forecast to grow.

“The major growth area among hydrocarbons is petrochemicals,” says FGE’s Sawyer. “Demand for naphtha and LPG [liquified petroleum gas] will increase significantly, but if you look at the supply, there is an increasingly large supply coming from non-refinery sources.” For example, ethane from shale deposits is being used as petrochemical feedstock, and there is a significant amount of LPG coming out of crude oil production, rather than from refineries, as well as the inclusion of biofuels and other oxygenates into fuel formulations.

For every 100 barrels of oil in increased demand, there might be only 60 barrels of that coming from a refinery, Sawyer says.

“The future of refining is how they are going to adapt to that. Not only are they challenged to manage the molecules, but also to manage the assets they’ve got, such as logistical infrastructure, tanks, real estate and so on, to play into the market that is developing,” Sawyer explains.

“This is what refiners have done for 100 years, but the challenge is big and it’s right in front of us,” he notes. Refineries are not dead — out to 2040, there will still be oil demand for 100 million bbl/d, Sawyer says, so refineries will still play a role, but it might be a smaller one. “So that begs the question of what level of investments should be made and what kind of investment should it be and where, and so on.”

IMO update

The beginning of 2020 also saw the start of the anticipated regulations from the International Maritime Organization for sulfur levels in shipping fuels, reducing the allowable percentage from 3.5% to 0.5%. For more on the IMO order, see Chem. Eng., May 2018, pp. 16–20.

After a sluggish start in 2018, when the IMO fuel sulfur limits were announced, there was quite a bit of action in 2019, as over 2,000 sulfur emissions scrubbers were retrofitted on existing ships by the end of 2019. The number will rise in 2020 and 2021. Newly built ships will be fitted with scrubbers, or will have the space and the tie-ins to add them easily.

Onboard scrubbers for sulfur emissions make good economic sense when the price differential between high-S fuel and low-S fuel is sufficient to justify the investment. That difference has been there, von Berkel says, but COVID-19 has pushed down crude prices, so the differentials between low-S and high-S fuels are correspondingly smaller. “So the investment [in scrubbers] is still acceptable, but it’s not as ‘sexy’ as it was a few months ago,” von Berkel says.

“Up until Q1 of this year, demand has not been that great for the low-S bunker fuels, because people wanted to burn the cheaper, high-S fuel for as long as they could,” von Berkel explains. And refiners have generally not invested heavily in making low-S bunker oil. “So the supply of low-S fuel has not been tested. We have to wait for the true supply and demand picture until later this year, but the deadlines went by without a hitch.” n

Innovation and digitalization

As refiners try to weather the current public health crisis along with the rest of the world, they are also looking to the future. And a big part of what will shape the future is innovation. A few recent developments on that front include advanced catalysts, R&D capability and digitalization.

Crude laboratory. In January of this year, Clariant Refinery Services (Houston, Tex.; www.clariant.com) opened a new state-of-the-art crude and fuel oil laboratory that focuses on applications for transport and storage. Based in Bradford, U.K., the laboratory supports a highly experienced technical services team equipped to address multiple challenges experienced by refineries, storage terminals, pipeline providers and logistic companies around the world, Clariant says.

The new laboratory has a wide selection of testing regimes and modern methods of crude oil analysis and performance testing. One focus on the facility will be to identify and develop new and customized pour-point depressant (PPD) solutions for the downstream and midstream sectors. Researchers at the laboratory have already developed PPD products and fuel stabilizer solutions specific to the challenges presented by the International Maritime Organization (IMO; London, U.K.; www.imo.org) 2020 regulations, limiting marine fuels’ sulfur content to 0.5% from the previous limit of 3.5%.

FCC catalyst. BASF SE (Ludwigshafen, Germany; www.basf.com) launched Fourtune, a new fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) catalyst product for gasoil feedstock. The catalyst is designed to deliver superior butylene over propylene selectivity, while maintaining catalyst activity and performance.

Commercial trials of Fourtune have confirmed its ability to deliver better economic performance through butylene selectivity and high conversion, the company says, and it maintains coke-selective bottoms upgrading and high distillate yields that increases refiners’ profitability.

Fourtune is the latest product based on BASF’s Multiple Framework Topology (MFT) technology. BASF’s MFT technology enhances performance through the use of more than one framework topology that work together to tailor the catalyst selectivity profile, BASF says. Evaluations of the new MFT technology have demonstrated Fourtune’s ability to help maximize margins and provide operating flexibility to make more butylene to feed the alkylation unit.

AI refinery project. Artificial intelligence (AI) technology is set to become more widely used in the refining industry. A partnership between BP plc (London, U.K.; www.bp.com) and Beyond Limits (Pasadena, Calif.; www.beyond.ai) has resulted in an “operate-to-plan” project using AI at a BP refinery.

“In many cases, a linear plan for a processing unit is not realizable initially, so engineers have to make it work on the ground, based on what is happening in the plant,” explains Kim Gilbert, director of technical sales engineering at Beyond Limits. The AI project started on a naphtha unit with 8–10 distillation towers. The objective was to use AI to help the plant engineers implement their linear plan from AspenTech. The AI software, which was developed from technology licensed from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, is using machine learning to identify anomalies and long-term patterns in the data, and connect them to explanations that make sense to operators.