Understanding project risks is critical to arriving at useful cost estimates. Since each capital project in the chemical process industries (CPI) is somewhat unique, it can be difficult for engineers and project leaders to price risks in their estimates and project budgets. This one-page reference provides information on project risk, contingency and accuracy in cost estimation.

Cost estimates include two main parts: the “base,” which encompasses the risk-free costs, other than specific allowances, and the “risks,” which include contingency, reserves, escalation and currency exchange.

Definition of terms

The following terminology is associated with cost estimates and risk.

Risk. An uncertain event or condition that could affect a project objective or business goal.

Base estimate. Estimate including allowances, but excluding escalation, currency risk, contingency and management reserves.

Allowances. Resources included in (base) estimates to cover the cost of known, but undefined, requirements for an individual activity, work item, account or sub-account.

Contingency. An amount added to allow for items, conditions or events for which the state, occurrence or effect is uncertain, and that experience shows will likely result, in aggregate, in additional costs (this excludes major scope changes, catastrophic risk events and conditions, escalation and currency risk).

Management reserves. An amount added to an estimate to allow for discretionary management purposes outside the defined scope of the project, as otherwise estimated. May include amounts that are within the defined scope, but for which company leadership does not want to fund as contingency, or that cannot be effectively managed using contingency.

Escalation. A provision in costs or prices that accounts for uncertain changes in technical, economic and market conditions over time. Inflation (or deflation) is a component of this.

Accuracy range. An expression of an estimate’s predicted closeness to final actual costs or time. Typically expressed as high or low percentages by which actual results will be over and under the estimate (base or funded), along with the confidence interval that these percentages represent.

Estimation accuracy

A capital cost estimate is expressed as a range of possible costs, rather than a discrete “number.” Effective cost estimators work to understand (and be honest about) the details and factors that they do not know. Those preparing estimates must communicate the project risks, the range of possible outcomes and, most importantly, how those two go together.

Accuracy ranges are expressed as low and high percentages that form a boundary around the expectation of how final actual costs will differ from the estimate. For example, a range of +30%/–10% tells management that the final costs may be as much as 30% more or 10% less than the estimate after taking into account all of the identified risks. To be complete, range statements should inlcude the confidence in the range. (for instance, stating that 80% of the time, the project will be within these bounds). It is also important to specify the reference point upon which the range is based (it can be relative to the base estimate or to the funded amount, including contingency).

Scope definition and risk

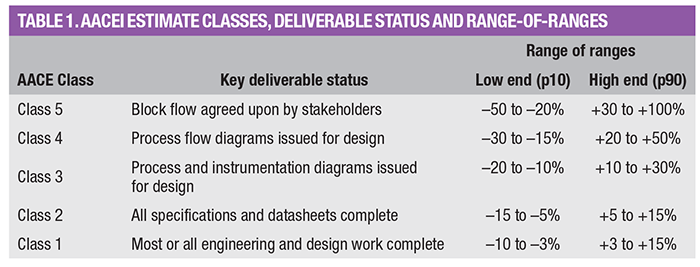

The level of scope definition is the greatest driver of cost uncertainty. Estimate accuracy improves with the level of scope definition. Since the 1990s, almost every major CPI owner company has implemented a phasegate project system, and the phases usually line up with the Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering (AACE) International (Morgantown, W.Va.; www.aacei.org) AACE Estimate Classes (Table 1). Other key risk drivers within the project scope include the introduction of new technology into the process and the level of complexity in the physical system, as well as the execution strategy.

Bias

Capital project management is a realm of intense cost pressures and biases. If high estimates scuttle project sanction, the estimator’s performance rating and career development may be put at risk. In slow economic times, cancellation of a large project may mean the loss of the team’s jobs. For decision makers, optimism bias often prevails. For many reasons, the desire and pressures to make a “go-ahead” project decision can be immense. The more strategic the project, the more these biases create pressure for lower cost estimates, resulting in discrepancies. On the other hand, overruns may be punished, and this drives conservative estimating practices by those afflicted, particularly in small project systems.

These biases and their effect on estimating behavior are major sources of cost uncertainty. If the bias is toward decreased base estimates, more contingency will be required, and vice-versa if the bias is toward increased base estimates.

Editor’s note: This column is based on information found in Hollman, J., Improve Your Contingency Estimates for More Realistic Project Budgets, Chem. Eng., December 2014, pp. 36–43.