Chemical engineers bring many essential skills to the diverse teams required for successful control room design

In any continuous manufacturing plant in the chemical process industries (CPI), engineers need to consider control room architecture and design as part of their responsibility. Chemical engineers may think that this is not their area of expertise, and therefore not their responsibility. This is understandable, but this article explains why engineers should spend time thinking about control room architecture.

Chemical engineers spend their careers making the world a better place. They may develop new products and materials, manufacture existing products, recycle waste or clean the environment and create energy. Design and architecture are not typically their strong suits, and indeed they may not have given much time to understanding the configurations that make a control room safe, efficient and productive. However, architecture and design have a profound effect on how one executes the demands of his or her profession.

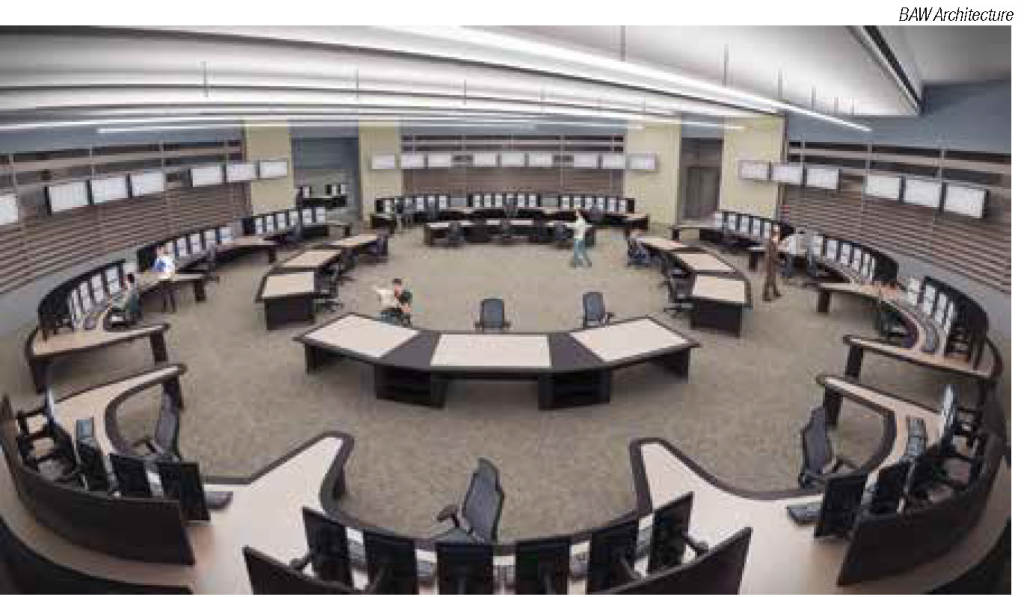

The reality is that it takes more than four walls and some fancy desks to design a control room that will last a generation, be an environment where operators can safely manage the chemical processes and where teams of people can collaborate to solve problems quickly and keep the plant running efficiently (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Many of a plant’s most critical operational tasks take place in a control room. A thoughtfully designed control room will enable collaboration, safe operations and ergonomic working conditions

That’s not to say chemical engineers need to come up with all the answers — there are architectural firms that specialize solely in control room design of the highest caliber — but there are a number of reasons why knowing how to ask the right questions is in chemical engineers’ best interest.

The operator

Demographics are such, particularly in North America, that plants are losing the most experienced operators to retirement faster than new personnel can be hired and trained — the latest generation of workers seem to have different aspirations and motivations for their careers. In the last 30 years, we we have greatly improved understanding of how operators worked and reacted to situations, but that experience and research applies mainly to an older generation. We simply do not know enough about what will change with a younger generation of operators. For this reason alone, when planning how the process will be controlled, it is essential to ensure that the room is designed from the operator outward. You should be asking: “What environment will ensure that the operator is comfortable, has a high situational awareness and is empowered to make the decisions necessary to operate a safe plant?”

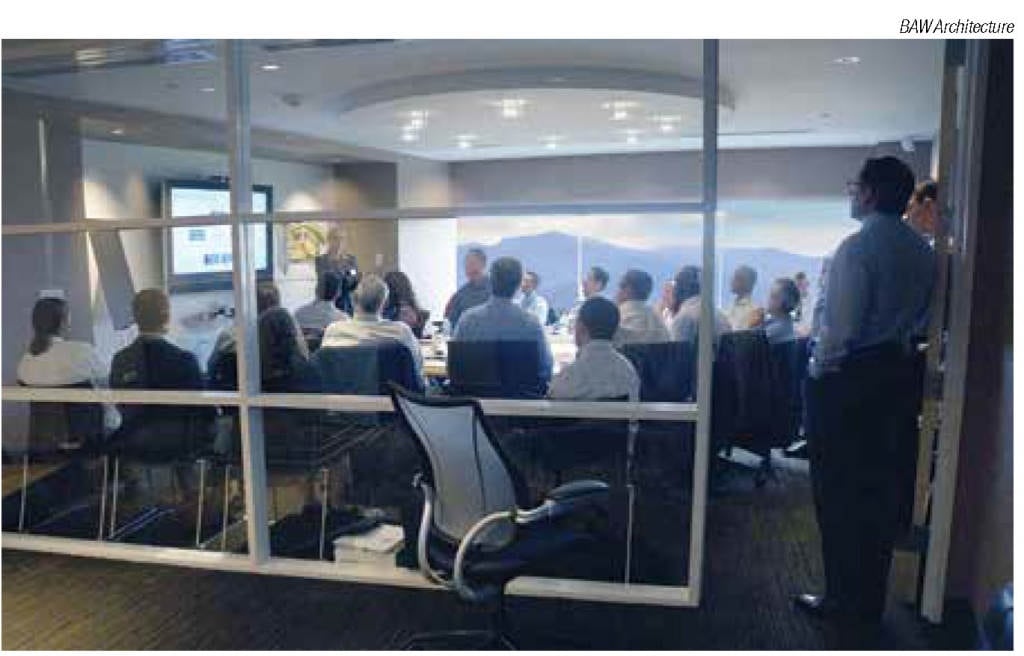

A best practice often used is a charrette (Figure 2). A charrette is a workshop-style meeting that is used to gather structured information from operators and other stakeholders from which the building blocks of the new facility take shape. The goal is to achieve consensus by the end of the three-day process on a block plan direction. Integration of best practices in control room design is woven throughout the approach. Human factors engineering (HFE) is an integral part of the control room charrette, and the data gathered during this phase informs the control room layout, control system and console design.

Figure 2. A charrette meeting is useful in planning control room projects in that many different stakeholders with diverse backgrounds can contribute their input and reach consensus on important goals

The operator is key to the successful design of a control room (Figure 3). His or her input is invaluable throughout the entire design process. Beginning in front-end engineering design (FEED), the operator should be engaged in design charrettes all the way through 100% design completion, and consulted for such items as workstation design, screen graphics and the human machine interface (HMI). Understanding the operators’ needs — mainly, how they interface with complex systems within a high-pressure environment — is “square one,” and all other design decisions flow out from that pivotal point. The most successful control buildings have been designed with the operators involved as part of the team from the project commencement.

Figure 3. Seeking operators’ input is extremely valuable throughout all phases of control room design

Collaboration

No matter how strongly individuals excel in chemical engineering, no organization can survive without collaboration. One of the key insights to harnessing collaboration is diversity. Experiments have shown that groups composed of only highly adept members are outperformed by groups with members of varying skill levels and knowledge [ 1].

While having a team made up of a number of brilliant engineers seems desirable, encouraging a diversity of perspective will help ensure an optimal outcome as you plan for a new control room or a control room renovation. To that end, it is recommended that input be solicited from not only chemical engineers, but also from automation engineers, control engineers, human factors specialists, designers, architects and, of course, operators.

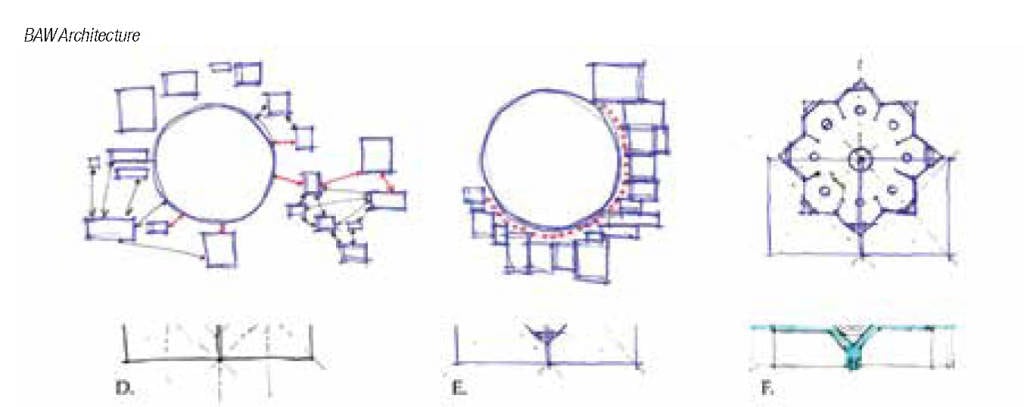

As part of this collaboration, one best practice is allowing sufficient time in the FEED phase to adequately plan and design a control room by integrating human factors engineering and the ISO 11064 standard, which spells out international standards in control room design [ 2]. This ensures that before the project gets too far down the road, risks and tasks are analyzed, and adjacencies and future expansion needs are identified. Drawings are produced and revised until consensus is reached (Figure 4). To have upper management commitment — and better yet, an HFE champion and liaison from the company on board to work with the team from the beginning and throughout all phases of the project — offers the most successful approach to control room design.

Figure 4. Allowing sufficient time for front-end design work, including conceptual sketches and human factors engineering, can save time and reduce costs as the control room project progesses

Involving HFE early in the FEED stage to provide expertise at the beginning lays a solid foundation for the development of the successful design. Involving a diverse collaboration team in decision-making throughout the process makes for a stronger design solution and allows for their early buy-in. Designing the work environment ergonomically to suit the operator is proven to reduce human error, accidents and illness, and designing it correctly the first time by utilizing the expertise of an HFE and control-room architect can save costly redesign efforts after the building is up and running. The 1:10:100 rule of thumb is often used when engineers are evaluating product quality. Through experience and case studies, we can also apply this to control room design. In short, if it costs $1 to fix a usability problem during design, it will cost $10 to fix once the system is developed, and $100 to fix once it is operational.

ISO 11064 recommends an iterative review process for the design of control buildings involving operators and engineers that will be working in the control room in meetings and decision-making. It leads the design work toward the best possible solution, and will create buy-in and a sense of ownership in the design.

In these meetings, participants need to identify risks associated with design. Some examples of these risks are the following:

- The control room is not designed to current ergonomic standards

- The design does not include enough area for potential future expansions

- If the building is in a remote location, not having skilled workers to provide construction labor

- Poor onsite security

- Poor communication because of multi-cultural teams

Effectively collaborating when planning a new control room will help on many fronts. The key aspect of having a diverse team (including chemical engineers) planning, reviewing and iterating on the design of the control room will ensure that the final product is one that everyone can agree on, and that optimizes the safety, situational awareness, job satisfaction and productivity of the site.

Change management

Organizations are often good at managing technical change. Chemical engineers must follow very specific change-management procedures when making any changes to manufacturing processes. Why do we put so much effort into this area? It’s simple: change-management systems and processes help to ensure that process and technical changes are risk-assessed so that fewer unforeseen consequences occur.

Organizations often do not apply the same level of change-management scrutiny to organizational changes. Implementing a new control room or control room renovation may involve some technical change, but we need to remember that the organizational change elements can be far greater for the employees. As such, the organizational change also must receive comprehensive planning, risk-assessment and management through the transition to make sure to reduce the risks related to major accidents. The key success factors for managing organizational change are as follows:

- Effective planning for the organizational changes

- Communicating with and involving key site personnel

- Assessing the risks relating to the change, including both risks from the process of change and risks from the outcome of the change

- Introducing and monitoring the change as it transitions

Furthermore, specific change-management preparation for staff includes the following:

- Providing upfront technical training to prepare for new systems

- Selecting and nurturing a highly respected project team

- Preparing leaders to lead the change in their areas and to collaborate across enterprises and departments

- Following a disciplined change process

- Sustaining new positive behaviors after implementation

Chemical engineers certainly understand the importance of solid change management, and their experience is essential to help support the organizational change management that is necessary for planning and adapting to a new control room or renovation.

Steps to success

Following a set methodology, each control room design process — for both new construction and renovations of existing facilities — can deliver exceptional and tangible results. When a project need is identified, a design team is formed. The makeup of that team can facilitate the project process. An experienced control-room design team integrates lessons learned and best practice knowledge for the new facility. The design is fine-tuned throughout the design process based on feedback from many parties. As a result, the control room will have received input from operators, staff and key project stakeholders, often including chemical engineers, and is a multi-disciplinary collaborative creation.

Build a great design team. The motivation to design or renovate a control room usually begins with operations, but is mostly decided by company leadership. Engaging an experienced architectural team consisting of architects, engineers, human-factors engineers and interior designers is an integral first step in the process. Understanding the value that a new or renovated control room can bring to an organization involves a comprehensive approach. The roles and responsibilities of each discipline, described below, are a vital piece to a complex puzzle:

- Architect: oversees the overarching concept and the design team (including structural, mechanical and electrical considerations, among others) and keeps the project on course

- Human factors engineer (HFE): ensures a human-centered approach based on ISO-11064 and industry best practices

- Interior designer: integrates all the disciplines together into an operator-centric, ergonomic and functional environment

Hiring experts in the design of control buildings ensures the building will be designed correctly the first time, reducing human error, avoiding costly renovations, accidents and illness related to poor design. Together, the team of specialists works collaboratively to design a control building that meets the needs of the operator. Lastly, an experienced building contractor can make or break the project by providing cost and schedule control to keep the project on budget and on time, as well as risk mitigation so that the job site stays safe. Collaborating with the owner and architect, the contractor turns the team’s vision into a reality.

So the next time there is talk of designing a new control room or renovating an existing control room at your organization, remember the reasons why you should get involved — the operator, collaboration and change management. What these three areas have in common is the need for a cross-functional approach to job design, work design and planning and implementation, all focused on improving process safety, efficiency and productivity.

Some additional lessons learned from the authors’ extensive experience in designing and building control rooms and buildings include the following:

- Allow enough time in FEED to start a control room project off right

- Workstations, as well as small and large screen placement, should be designed concurrently with the building design

- Incorporate area for future growth in the control room, rack room and infrastructure

- Communication and collaboration across the design team and with operational staff (including chemical engineering) and the construction team is key to successful organizational change and control room design.

Edited by Mary Page Bailey

References

1. Goman, Carol K., Seven Insights for Collaboration in the Workplace, Reliable Plant, April 2010.

2. International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 11064, Ergonomic Design of Control Centres, November 2013.

Author

Brad Adams Walker is an architect and founder and owner of BAW Architecture (300 South Jackson Street, Suite 430, Denver, CO 80209; Phone:303-388-9500; Email: [email protected]; Website: www.bawarchitecture.com). He completed his first control room design in 1987 and founded BAW Architecture in 1992. Pushing the boundaries and conceiving new operator-centric configurations in control room design led to commissions that earned him international recognition relatively early in his career. Since then, Walker has completed over 100 built control-building projects over the past 25 years for several global petrochemical companies. He is a distinguished speaker who has made presentations at numerous conferences related to optimal control room and control building design.

Brad Adams Walker is an architect and founder and owner of BAW Architecture (300 South Jackson Street, Suite 430, Denver, CO 80209; Phone:303-388-9500; Email: [email protected]; Website: www.bawarchitecture.com). He completed his first control room design in 1987 and founded BAW Architecture in 1992. Pushing the boundaries and conceiving new operator-centric configurations in control room design led to commissions that earned him international recognition relatively early in his career. Since then, Walker has completed over 100 built control-building projects over the past 25 years for several global petrochemical companies. He is a distinguished speaker who has made presentations at numerous conferences related to optimal control room and control building design.

Peggy Hewitt is an independent consultant providing business-development support to BAW Architecture (Email: [email protected]). Before working at BAW Architecture, Hewitt spent over 30 years at Honeywell in four industrial business sectors. While there, she led the ASM Consortium, a group of leading companies and universities involved with the process industries that jointly invested in research and development to create tools and products designed to prevent, detect and mitigate abnormal situations that affect process safety in control-room environments. Recently, she was interim vice president of membership at the Clean Energy Smart Manufacturing Innovation Institute (CESMII). In partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy, CESMII brings over $140 million in investment to improve the precision, performance and efficiency of U.S. advanced manufacturing.

Peggy Hewitt is an independent consultant providing business-development support to BAW Architecture (Email: [email protected]). Before working at BAW Architecture, Hewitt spent over 30 years at Honeywell in four industrial business sectors. While there, she led the ASM Consortium, a group of leading companies and universities involved with the process industries that jointly invested in research and development to create tools and products designed to prevent, detect and mitigate abnormal situations that affect process safety in control-room environments. Recently, she was interim vice president of membership at the Clean Energy Smart Manufacturing Innovation Institute (CESMII). In partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy, CESMII brings over $140 million in investment to improve the precision, performance and efficiency of U.S. advanced manufacturing.