Seven methodologies are described to help operations staff take greater ownership of asset performance

The definition of ownership — to act as an owner — implies certain responsibilities. Consider the range of behaviors demonstrated by individuals when it comes to the automobiles they own. For some, car ownership leads to a relentless pursuit of caring for every aspect of the car, from operation to maintenance. For others, it is a daily wish that their cars will simply start when the ignition is engaged. The outcome of the diverse behaviors along this continuum of ownership will have a direct impact on the reliability, longevity and cost of ownership of these complex machines.

Throughout the chemical process industries (CPI), owners of complex, costly machines and systems (assets) tend to act along this same continuum. In general, CPI operators typically want to ensure the delivery of performance levels in terms of three important measures — reduced lifecycle costs, improved reliability, and increased longevity before replacement. However, different individuals will go about achieving these objectives in different ways. Within any CPI facility, the quest to ensure reliability is thought to require three partners — personnel from the operations, maintenance, and engineering Depts. All three sets of individuals play vital roles in helping the asset to meet its important objectives, via their interactions throughout the lifecycle of each asset.

The efforts of the engineering department should be building in reliability since the design itself has a greater impact on reliability compared to the efforts by maintenance and operations depts. combined. For many, maintenance department efforts are thought to be the primary element responsible for the reliability of the installed assets. However, from our knowledge of various paths for equipment failure (the majority of which are random in nature), it turns out that operations personnel hold the key to delivering optimal business objectives, through their efforts related to the ongoing operation of the assets.

To further explain this important concept, we must first understand the “bathtub curves,” developed by Nolan and Heap in the 1960s and 1970s [ 1 ], which have driven maintenance practices in the airline industry for decades. The authors developed six failure curves that demonstrate how the probability of failure is a function of run time for machine components. The major finding was that 89% of these failure modes occur randomly — often with little to no warning.

At the time of these findings, industry’s approach to maintaining industrial and other assets had been to rely heavily on preventive or time-based activities, such as planned overhauls. However, given that the majority of failures occur randomly, it is not practical to expect that a time-based approach to equipment maintenance will detect or identify all potential failures. While online monitoring options can provide a close proxy for realtime surveillance in some instances, we cannot place a mechanic at each machine to constantly monitor its condition on a realtime basis. The operations department is the only group with enough continual exposure to the assets on the plant floor to be able to detect the earliest signs of many impending failures. So why do many CPI facilities still experience relatively high levels of reactive or breakdown-related maintenance, and fail to effectively deploy their operational personnel to provide close ongoing surveillance of the assets in the field?

Operations ownership In recent decades, there has been a transition in operations department culture. Many retirees lament the bygone era when operators knew not only how to operate their equipment but also understood how to maintain the function of all of the assets under their command. Historically, operators relied on using their four senses (hearing, seeing, touching and smelling) to keep close track of how the equipment was operating during their shift. They would adjust settings, add oil or grease, unplug and monitor their equipment and be able to detect small changes in the equipment condition and rapidly report their findings to the maintenance department Some even performed minor tasks to fix a problem early so as not to allow it to grow into a major downtime event.

However, more recently, that culture has slowly been replaced with a new mindset about the appropriate division of labor — that “operations personnel run the equipment” and “maintenance personnel fix the equipment.”

Nonetheless, today, due to the complexities associated with maintaining complicated equipment and support systems, participation by both of these functions is essential. In some industries, operating personnel have become “more comfortable” with elaborate control systems and control rooms, which took the operator’s exposure away from the equipment in the field. This drove an additional “wedge” into the culture of ownership needed to maintain equipment reliability. Now the question is, how do we return a state where operations personnel are once again empowered to be a critical partner — and allowed to take more of an ownership role — in the quest to maintain the asset base, as needed?

The path forward Back in the 1950s and 1960s, management did not have to present much of a business case for operations personnel to perform all of the tasks that are required to maintain equipment. Operator rounds and minor maintenance were an accepted part of the job description. Today, owners must develop more of a business case to justify the use of operations personnel for such tasks, allowing them to act like the true owners of their equipment assets.

The path forward involves “selling” the benefits of more direct ownership by operations personnel. These include a more predictable and safer work environment for all personnel, improved business targets for cost savings, higher overall productivity (through reduced downtime and higher asset optimization), and the development of new skill sets for plant personnel.

The business impact of these added operations department efforts should be demonstrated, by tracking metrics that are related to key business results. However, to be fair, the tracking should involve only business results that operations personnel could actually influence directly. Too often, management tries to translate the impact of operations department efforts using metrics that may be too strategic — such as mechanical availability and mean time between failures (MTBF) — and thus cannot be impacted easily by operations personnel actions. To be successful, this path forward also requires changing the mindset of company and plant managers, to establish metrics that really show the performance of operations personnel in the care of the equipment, and are thus attainable by operations personnel.

“Normalization of the abnormal” occurs when sub-optimal equipment conditions are tacitly accepted by those who operate the equipment. Left uncorrected, these sub-optimal conditions typically lead to reactive maintenance cultures, since the early signs of failure are not acknowledged and used to drive proactive repair. For instance, a valve that has “always been hard to close” is often taken for granted, until one day it does not close at all. Once the “new normal” state of equipment conditions are established (the valve is replaced), the early detection of potential failure modes can be recognized.

The importance of the need to recognize early signs of failure should be driven to the floor-level personnel, so they can quickly recognize failure and request repairs when they have the smallest impact on overall plant operation. This involves using periodic audits and basic troubleshooting tools, and providing accurate descriptions of what equipment requires repair. Operations personnel should be encouraged and allowed to return to performing basic and simple repairs (so-called autonomous maintenance). This approach will allow maintenance personnel to focus on performing proactive, strategic care tasks that are designed to move the facility away from reliance on reactive maintenance. In general, reactive maintenance often engenders higher costs, more downtime, and a workplace that is less safe overall.

Detailed below are several methodologies that can help drive a more-effective partnership between owners and the operations department Each of these is discussed in greater detail in the sections that follow: (1) Developing the value proposition; (2) Establishing metrics; (3) Changing the equipment-condition mindset; (4) Training and troubleshooting; (5) Integrating maintenance work processes; (6) Conducting operator rounds; and (7) Increasing autonomous maintenance. No single methodology will secure the role of the operations personnel as owners of the assets, but efforts to include operations personnel more completely in the care of the assets will eventually deliver the desired results.

1. Developing the value proposition.In general, a value proposition is a business or marketing statement that summarizes why an individual consumer should buy a product or use a service. This statement should convince a potential consumer that one particular product or service will add more value or solve a problem better, compared with similar offerings. The ideal value-proposition statement is short and appeals to the customer’s strongest decision-making drivers. It is important to make sure operations personnel understand all of the reasons why they should take a more active role in equipment-care activities.

Management should first focus on “selling” operations personnel on the potential benefits of joining their colleagues in maintenance and engineering depts. in the pursuit of more reliable operations. Historically, management has told operations personnel that their primary job was to ensure that the manufacturing process is operated within the acceptable range of key operating variables — such as temperature, pressure and so on.

Historically, operations personnel have stressed that their first responsibility is to operate the process in a safe manner. They are also tasked with data recording and meeting responsibilities. One can argue that some of the data they are recording during operator rounds — for instance, “Is the pump running?” — are a form of “management control” and may not even be reviewed by supervisors. Some operators do not understand what the data tells them and they question why such data are being recorded at all. Based on this background, it is no wonder that for many operations personnel, equipment monitoring often takes “a back seat” to other responsibilities and they may not understand its full value in influencing asset reliability.

Appropriate monitoring of equipment and providing basic care does improve the operating environment for operators, and will help to achieve many safety, productivity, and cost goals that are established by management. In many facilities, operators are hoping for a predictable work shift, where the process is running at steady state with little variation and upsets. Processes that are not reliable tend to call for reactive maintenance, which contributes to unsafe behaviors. Thus, a useful value proposition for CPI operators may be expressed as follows: For operators of CPI assets who want to work in a safe and sustaining environment in order to provide for their families and loved ones, reliable operations require a day-to-day focus on reporting out-of-range conditions, recognizing the early signs of equipment failure, troubleshooting loss of function, recording required data, and looking out for each other’s safety.

Management needs to reinforce that safety, sustainability and predictability are the strongest drivers in all CPI operations. These words — and concepts — should be constantly reinforced at all levels of supervision, and should appear on information boards throughout the facility and be stressed at daily meetings. A small portion of the operations group will already understand the message, while another portion of the Operations group will require some evidence to get them involved.

2. Establishing metrics. The adage “What gets measured, gets improved” is heard throughout the business landscape. However, metrics can be a double-edged sword and sometimes individuals and groups can become bogged down by “paralysis by analysis” when excessive metrics are tracked, but for no clear purpose. Nonetheless, tracking of appropriate metrics can drive behaviors. People adjust their behaviors based on what aspects of their performance are being measured. For instance, if plant personnel are evaluated for process uptime alone, they may not make the best decisions about how they operate the equipment.

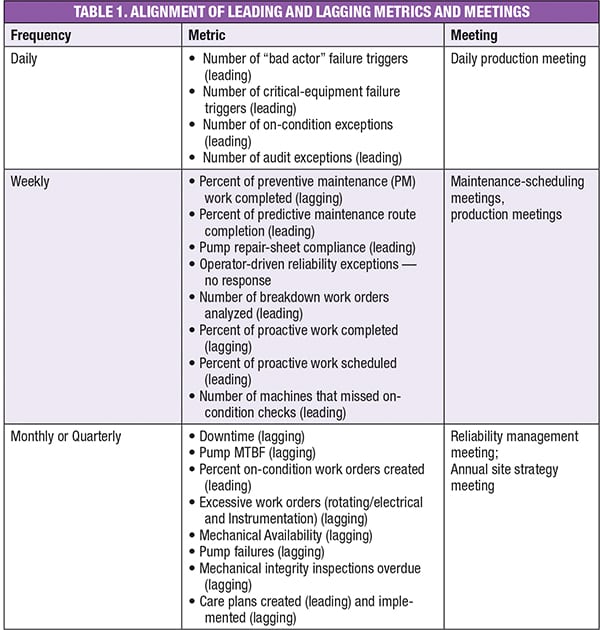

Tracking the right combination of metrics can propel an organization toward desired targets for improvement, while focusing on the “wrong” mix can steer people toward contradictory actions and may lead to more inefficiency in terms of wasted costs or time. The “right” mix of metrics includes both “leading metrics,” which measure process activity such as the amount of practive work scheduled, and “lagging” metrics, such as maintenance-schedule compliance and mechanical available, which measure an outcome.

In general, lagging metrics are more strategic, and thus management tends to put disproportionate emphasis on them. However, operators are often not able to meaningfully impact these metrics. For instance, in the case of reliability, focusing on MTBF with maintenance and operations personnel generally draws blank stares. However, directing their attention to leading metrics, such as percent of work orders with work history, percent of scheduled lubrication routes completed, and percent of exception found on equipment monitoring routes, allows them to “move the needle” on plant operations that will eventually impact MTBF. Table 1 illustrates this concept further.

Table 1 also shows the timing of reporting leading and lagging metrics. Leading metrics should be discussed daily to weekly, whereas lagging metrics should be discussed weekly, monthly and quarterly, because the ability to change lagging metrics generally takes more time. Operations and maintenance personnel can become frustrated when seeing little movement in lagging metrics, when their focus should really be on “moving the needle” with those metrics they can impact directly over shorter time horizons.

3. Changing the equipment- condition mindset. As noted, “normalization of the abnormal” is the enemy of reliable operations over the long run. The acceptance of sub-optimal existing conditions, such as loose fittings, small leaks, tough-to-close valves, and many others represent the waiting room for failure. Unfortunately, these conditions become part of the landscape in many manufacturing facilities, and with the existence of higher-priority reactive work, they often never get fixed.

Operations personnel are exposed to these conditions on every shift. They often bring attention to these issues but get little response. When this pattern persists at a facility, it is difficult to recruit operators as partners in the pursuit of improved reliability, because they can point to many examples that indicate that management is not willing to fix items they report. The path forward is for management to demonstrate its commitment to remediating these early signs of failure, as a proven way to forestall larger problems later.

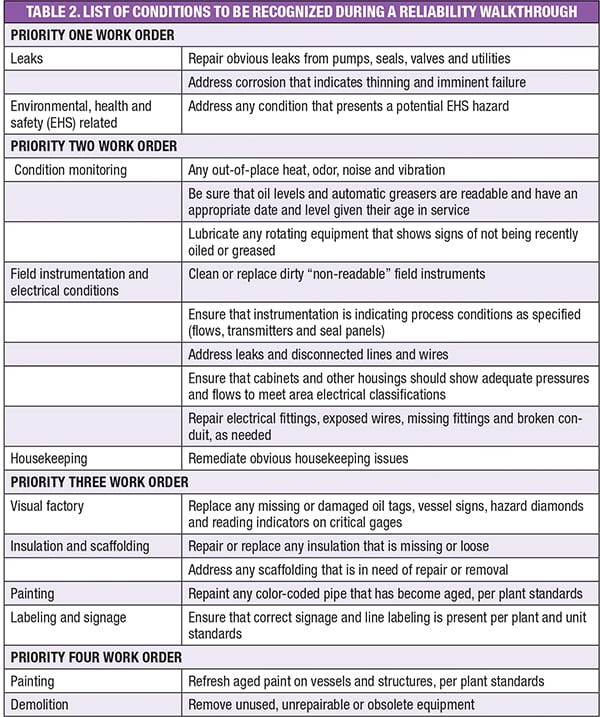

One useful method to deploy is the reliability walkthrough. Just as many manufacturing operations perform safety walkthroughs of their units, another set of audits should be performed to monitor equipment condition. Plenty of preparatory work is required before starting. The first step is to gain buy-in with production management to perform these audits. Such buy-in can be gained by showing existing field evidence of conditions that require repairs, such as missing conduit covers, bad valves and missing oil containers. Recognizing a prevailing lack of attention toward equipment is vital to encourage a change in attitude. Leveraging management’s commitment to improving reliability is another.

Once buy-in is achieved, the maintenance and reliability departments need to set up a standard for what conditions are considered abnormal, and make it a priority to fix these conditions in accordance with the existing maintenance execution process (Table 2).

Next, establish a schedule for these audits. Participation should include Production management, operators, maintenance or reliability engineers and maintenance personnel. One attendee is assigned to be the scribe to record what is found and set the priorities for the work.

After the audit, the list is converted to work-order requests. These audits should be more than just a “fix-it” tour. They should represent a culture-changing event so that over several months of audits, operations personnel will begin to better understand what represents acceptable equipment conditions. They begin to see management’s commitment to improved reliability and safety. Eventually (after a year or so), a variety of metrics are used to show progress.

Relevant metrics include percent reactive work, percent mechanical availability, percent process uptime and MTBF. Consistent effort will generally show improvement across all classes of assets, especially when participants demonstrate patience, commitment and consistency. Consistency is important — plant personnel must avoid the temptation to postpone audits due to other demands or priorities, attendance issues, weather, and downtime.

4. Training and troubleshooting. Operator training is often restricted to safety and process-operations- related areas. For operators to progress to increased levels of responsibility, they generally focus on improving their breadth of unit knowledge, achieving better process understanding and developing increased analytical capabilities. However, often left out of the training is attaining improved understanding of equipment operation. Also, understanding the principles related to pressure, temperature and flow measurement may not be part of their training matrix. And yet insufficient training in these topics can lead to failure in CPI operations. The majority of failures in the manufacturing environment result from how the equipment is operated. Examples include improper pump operation, running equipment outside of design limits, improper setup, lack of lubrication and missing needed adjustments, to name a few.

A lack of understanding of machine operation is another hurdle facing operations personnel. For operators to partner effectively with maintenance and engineering personnel, the first steps are to determine the gaps in their understanding of equipment operation, and related principles of pressure, temperature and flow. Any identified gaps should be included in the training matrix that is required for operator responsibility progression. Trainers may come from in-house engineers, maintenance personnel, training professionals, third-party vendors and even local colleges.

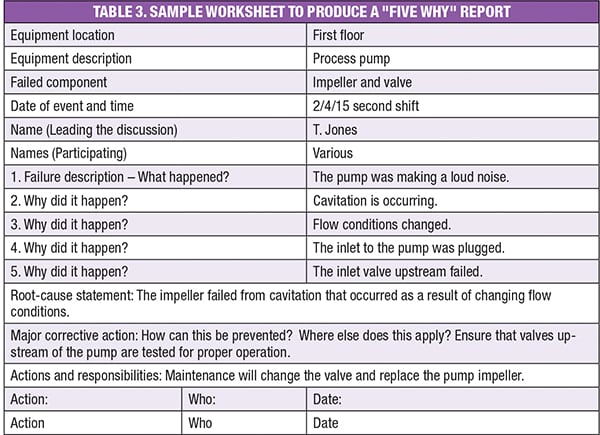

During training, the topic of troubleshooting deserves special attention. The aim is to drive troubleshooting to the floor level, so that problems can be solved quickly and avoid involvement from the maintenance department Such an approach benefits both maintenance and operations efforts. Operators should be required to perform basic troubleshooting from the first signs of variance from normal operations. One easy tool to use is a “Five Why” structure (Table 3). It requires the participant to question each observed result by asking “Why?” five times to drill down on the events that occurred, in order to identify a root cause.

Although the “Five Why” approach is limited in its application, it does apply to many situations faced by operations personnel. Oftentimes, operations personnel can resolve the issue themselves before calling their colleagues in maintenance. Even if they cannot resolve the issue, the information derived from the initial investigation and troubleshooting efforts will improve the content of work order requests, which will help maintenance personnel to be more efficient. Operations personnel should also be included as part of more formal root-cause investigations, as a participant, so they can contribute needed information.

5. Integrating maintenance work processes. A partnership is built on eliminating boundaries. Many manufacturing locations restrict operations department access to their computerized maintenance management system (CMMS). This barrier prevents operations personnel from executing their role in equipment care, potentially creating restrictions in submitting work requests. At some locations, operations personnel must contact a maintenance representative or a supervisor to submit work requests. This added step can restrict which needed work is performed.

In general, operations personnel should be given limited access to the CMMS. For example, operators should be able to submit work requests at any time. The maintenance department gatekeeper on the CMMS system will ultimately decide the priority of all submitted work requests. The site can set up a few logon identifications and terminals for access and provide operations personnel with access to view work orders and their status.

The quickest way to frustrate any initiative by operations personnel who are willing to participate in the care of the equipment is to not provide feedback to the suggestions they make. Giving operations personnel access to the CMMS will allow them to view and track the status of audit findings and other submitted work orders and suggestions they may submit.

The maintenance department also has a role to play in this partnership when it comes to work-order execution. For instance, work-order schedules should be distributed to operations personnel so they can prepare for the work to be performed. Priorities should reflect the current state of the operation department priorities. After responding to a work order, maintenance personnel should seek out the specific operations personnel with the work-order response to acknowledge their submission and ensure their satisfaction with the work and the condition of the area after the work was performed.

6. Performing equipment rounds. A widely held belief in industry is hat “Operators can fail the best designed equipment, but they can also run marginal equipment.”

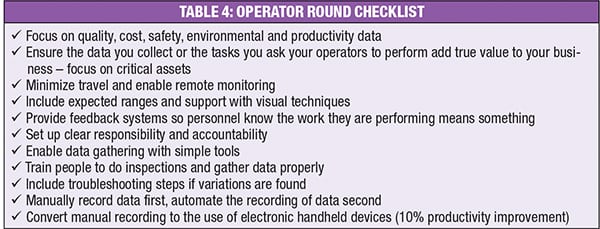

Some equipment-round sheets are no more than checklists and contain no standards to help personnel recognize abnormal operating conditions. Data are typically gathered by operators with little understanding of why it is important to the operations of the process. Periodic equipment rounds in some cases represent a form of “control” designed by supervision to keep people moving. Given this landscape, operators tend to “pencil-whip” (give a cursory effort but not complete) rounds as they may not understand their purpose.

To make equipment rounds most effective, operations personnel should always start with a focus on the critical assets (at least at the beginning), rather than all assets, to make best use of the time.

Useful data to be gathered in the field should indicate the “health” of the assets. The use of visual techniques will allow an individual to understand quickly if many types of equipment are operating normally. For example, note the expected range on a pressure gage and mark on the operator-rounds sheet whether that gage is operating within the target range. Ensure that someone is reviewing the operator-rounds sheets (or their equivalent in an electronic database) and that feedback is given when variances are observed. Table 4 provides a brief checklist that can be used during operator rounds so their efforts align with the recommendations discussed above.

7. Autonomous maintenance. The early detection of failures benefits chemical process operations through greater uptime, reduced maintenance costs and a safer working environment. As operators are closest to the daily operation of mechanical assets in a CPI facility, increased operator awareness and involvement in all reliability efforts is a key enabler to this early defense warning system for impending functional failure. Constant monitoring by these strategic personnel provides an opportunity to correct a variance before it has a chance to affect overall plant operations.

Even more advantageous to the facility is when relatively easy repairs can be made on the spot (involving such rudimentary tasks as tightening flanges, replacing packing and so on), rather than requesting maintenance department involvement and then awaiting their arrival. The time lost waiting for repairs can increase the cost of the repair and take maintenance personnel away from other proactive tasks that are needed to provide asset care.

Encouraging autonomous maintenance activities for certain tasks by operators offers one solution. Unfortunately, industry’s history with utilizing operators for these tasks has not always yielded a success story. Site-specific work rules, lack of training, lack of a value proposition, and “perhaps exaggerated” concerns for safety tend to keep operators from being allowed to handle these important tasks.

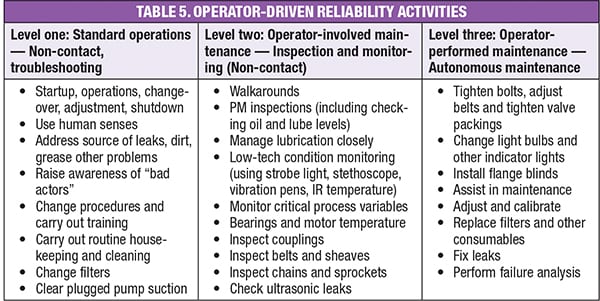

However, with strong management support, these obstacles can be — and have been — overcome at many CPI locations. First, a policy is needed to indicate which elements of corrective (autonomous), preventative and predictive care can be performed by operators, and then to establish buy-in among all affected parties. Maintenance personnel can be assured that operators are not trying to replace them. Staff support is needed to convert the appropriate preventive maintenance tasks to condition-based tasks for operators to perform. In fact, roughly 30% of preventive maintenance tasks can be done by operators. Table 5 summarizes the important steps that are needed to establish a multistep approach — one that recognizes three levels of possible operator-driven reliability activities.

The selection of which of these levels to perform will be a function of site needs, culture and operator skill level. As indicated in Table 5, operators in level one perform normal operating tasks along with non-contact tasks involving the four senses (hearing, seeing, touching and smelling). Of course touching can be done with limitations. In addition, the Level one group includes executing simple tasks, such as setup, cleanup, adjustment, alignment and checking that are required to ensure proper asset operation.

Level two tasks attempt to use operators for some condition-based tasks, including the use of some non-contact tools to diagnose asset condition. Lubrication is included in this level and will require the setup of a lubrication program (consisting of minimal selection of lubricants, establishing color-coded lubrication locations, establishing lubrication storage, and developing checklists that direct appropriate lubrication protocols). Performance of level two tasks does not require mechanical skills, perhaps just some rudimentary training.

Level three moves closer to the definition of autonomous maintenance, with operations personnel carrying out some basic care tasks, using a few select tools. What is important in this level is the inclusion of the expectation that the operations personnel will assist with the troubleshooting of equipment failures. Maintenance personnel will eventually come to view the assistance from operations personnel as a benefit to the overall mission of the facility; which is to maintain and restore safe, reliable function. In facilities that have adopted this approach, the maintenance department often remarks that consistency in the way in which the equipment is operated, monitored and maintained provides great benefits.

Closing thoughts Success in achieving site reliability is based upon the “triad” that is formed by a solid partnership between operations, maintenance, and engineering personnel, all performing their respective roles in applying the “right” practices throughout the life of all plant assets. No successful reliability effort can be accomplished without all three groups “pulling their weight.” Unfortunately, cultural norms within CPI operations often do not allow all parties to participate fully.

In particular, operations personnel often consider that their role is to “run” the equipment while maintenance personnel repair it upon failure. Nonetheless, operations personnel have the most direct and consistent exposure to the equipment over time, which gives them invaluable access to detect the early signs of potential failure. Thus, they can play a critical role in reducing machine failures. Each of the seven methodologies discussed here provides essential elements to help drive an operational excellence program, and promote greater cooperation among the three groups in the triad, in order to maximize safety and process uptimes while lowering operating costs. n

Edited by Suzanne Shelley

References

1. Nowlan, F. Stanley, and Heap, Howard F., Reliability-Centered Maintenance, National Technical Information Service, Report No. AD/A066-579, December 29, 1978.

Author

David Rosenthal is a reliability consultant with more than 35 years of experience, and owner of Reliability Strategy and Implementation Consultancy, LLC (2914 Ocean Mist Ct., Seabrook, TX, 77586, Phone: 215-620-2185; Web: www.reliabilitywithoutfailure.com; Email: [email protected]). He provides a wide range of maintenance and reliability consulting services, aimed at designing and implementing asset-care strategies to improve uptime and reduce operating costs. He previously led asset management services for Jacobs Engineering Group (Houston). Rosenthal spent the majority of his career with the Rohm and Haas Co., a specialty chemical manufacturer. During his 29-year career with Rohm and Haas, Rosenthal held roles related to maintenance leader, reliability leader, process and project engineering, and technical management in various facilities. In 2012, Rosenthal served as president of AIChE. He currently leads the Advisory Board to the Soc. of Maintenance and reliability professionals. Rosenthal graduated from Drexel University with a B.S.Ch.E., and holds an M.S.Ch.E. from the University of Texas. He is a registered professional engineer in Pennsylvania, and a certified maintenance and reliability professional (CMRP).

David Rosenthal is a reliability consultant with more than 35 years of experience, and owner of Reliability Strategy and Implementation Consultancy, LLC (2914 Ocean Mist Ct., Seabrook, TX, 77586, Phone: 215-620-2185; Web: www.reliabilitywithoutfailure.com; Email: [email protected]). He provides a wide range of maintenance and reliability consulting services, aimed at designing and implementing asset-care strategies to improve uptime and reduce operating costs. He previously led asset management services for Jacobs Engineering Group (Houston). Rosenthal spent the majority of his career with the Rohm and Haas Co., a specialty chemical manufacturer. During his 29-year career with Rohm and Haas, Rosenthal held roles related to maintenance leader, reliability leader, process and project engineering, and technical management in various facilities. In 2012, Rosenthal served as president of AIChE. He currently leads the Advisory Board to the Soc. of Maintenance and reliability professionals. Rosenthal graduated from Drexel University with a B.S.Ch.E., and holds an M.S.Ch.E. from the University of Texas. He is a registered professional engineer in Pennsylvania, and a certified maintenance and reliability professional (CMRP).