Passage of the Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act has created a long and challenging road ahead for U.S. EPA rulemaking

On June 22, 2016, the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act (LCSA) was signed into law with great fanfare as the successor to, and replacement for, the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which had not been updated since 1976. Among other provisions, the new law establishes a mandatory requirement for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA; Washington, D.C.; www.epa.gov) to evaluate the safety risks associated with existing chemicals, creates a risk-based standard for determining whether the use of a chemical poses an “unreasonable risk” and lays the groundwork for a consistent source of funding for EPA to carry out its responsibilities under the law.

On June 22, 2016, the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act (LCSA) was signed into law with great fanfare as the successor to, and replacement for, the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), which had not been updated since 1976. Among other provisions, the new law establishes a mandatory requirement for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA; Washington, D.C.; www.epa.gov) to evaluate the safety risks associated with existing chemicals, creates a risk-based standard for determining whether the use of a chemical poses an “unreasonable risk” and lays the groundwork for a consistent source of funding for EPA to carry out its responsibilities under the law.

Although the law has enjoyed widespread support from many stakeholders, the details of how the law will be implemented are presenting a host of challenges, both philosophical and logistical, for the EPA and for industry. Among these challenges are how to conduct chemical safety evaluations, how to prioritize the chemicals up for review, and what fees will be assessed to chemical manufacturers. Developments over the last few months have moved toward resolving some of the questions, but a long and challenging road remains ahead.

“EPA has a big job in front of it,” says Steve Owens, a principal with the law firm Squire Patton Boggs (Phoenix, Ariz.; www.squirepattonboggs.com), and a former EPA assistant administrator, “but virtually all of the stakeholders have been supportive so far, and [EPA] has handled it well to this point.”

“So far, everybody has been ‘on their best behavior’ with the rollout of this law, but it is still early in the process, and there could be a lot of friction in the rulemaking process,” Owens says. “There are four major rulemakings that need to be accomplished in one year, and that is very difficult to do, even under ideal circumstances,” he explains. Lawsuits, Congressional action, or other unforeseen developments related to an election-year transition to a new administration could hinder the effort.

Stakeholder input

In an environment of stubborn partisan opposition, the LCSA was a rare piece of legislation that enjoyed widespread support from both U.S. political parties, as well as from industry groups. The American Chemistry Council (ACC; Washington, D.C.; www.americanchemistry.com), an industry organization that supports the law, says “Thanks to the LSCA, America’s manufacturers will have the regulatory certainty they need to innovate, grow, create jobs and win in the global marketplace — at the same time that public health and the environment benefit from strong risk-based protections.”

Chemical producers are on board. Mark Silvey, senior manager for corporate and government affairs at PPG (Pittsburgh, Pa.; www.ppg.com) says “passage of the [LCSA]… has secured a much-needed overhaul of our nation’s chemical laws.” The modernized chemical safety law “puts the protection of human and environmental health and safety first, while also enabling America to retain its place as the world’s leading innovator,” he adds.

Environmental groups have also been generally supportive of the law’s intent to strengthen EPA’s authority to evaluate chemicals on a safety basis, and improving the existing TSCA law, which many have viewed as weak. However, some groups, including the public health advocacy organization Environmental Working Group (EWG; Washington, D.C.; www.ewg.org), think the law doesn’t go far enough.

While it acknowledges that the law makes significant improvements over the previous TSCA law, the EWG argues that the law “does not provide EPA with the resources or clear legal authority to quickly review and, if needed, ban dangerous chemicals linked to cancer and other serious health problems.”

Whether or not the law succeeds in its intent will be determined largely by how the rules and regulations associated with the law are developed, and the process of collecting stakeholder input for those rules is well underway. ACC says it wants to ensure that the rules developed under the LCSA are “written in a way that encourages effective and efficient implementation of the nation’s updated national chemical regulatory system.”

The EWG calls the rulemaking process for the LCSA “an unprecedented opportunity to perform robust risk evaluations and promulgate strong regulations to protect all Americans from the most toxic chemicals in our society.”

TCSA work plan chemicals

EPA action

Immediately after the June passage, the EPA issued its “First Year Implementation Plan” for the LCSA. EPA says it intends the plan to be a “roadmap of major activities EPA will focus on during the initial year of implementation,” but stressed that the plan would be a “living document” that is subject to further development over time.

In an effort to engage stakeholders early in the rulemaking process, EPA held a series of stakeholder meetings in Washington in August. One of the meetings dealt with determining which chemicals EPA would get initial risk evaluations by the agency. Another meeting focused on the agency’s general process and criteria for identifying high-priority chemicals for risk evaluation and how to prioritize other chemicals in the future.

ACC says “A draft prioritization rule must: clearly define the criteria for designating high and low priority chemicals based on hazard and exposure potential, conditions of use and other factors; provide timeframes for EPA to complete its work and for manufacturers to provide information to the Agency; outline a prioritization methodology that allows for the incorporation of new exposure tools and methods over time; and, include ample opportunities for stakeholders to provide comments and information to the Agency.”

The third stakeholder meeting had to do with the collection of fees to help defray the cost of implementing provisions of the law and fees for the costs of industry-requested risk evaluations. EPA acknowledges the importance of completing a rule on fees in a timely manner.

Public comment periods for those three topics closed in late August, and many groups did submit comments. The agency is now reviewing those comments in preparation for its draft rules in those three areas.

Initial risk assessments

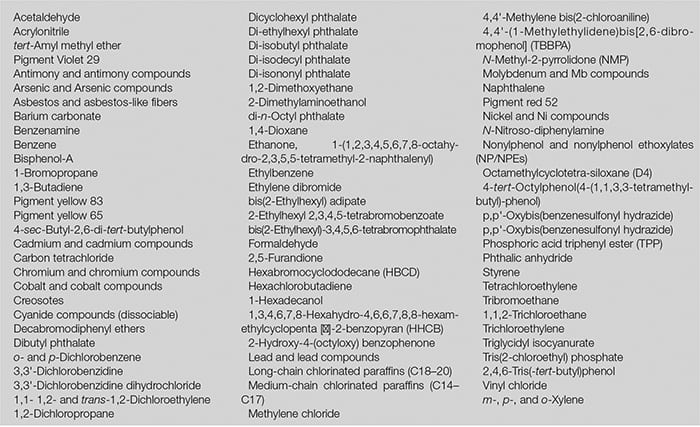

One of the major decisions for the EPA will involve which chemicals will be the subject of the first safety evaluations under the LCSA. As part of its implementation plan for LCSA, EPA will publish a list of ten chemicals on which it will conduct risk assessments, and formally initiate those studies. The list of the first ten chemicals, which EPA plans to reveal by mid-December, may be influenced by stakeholder comment, but will be drawn from a larger list established before the passage of LCSA. In 2014, EPA published a 2014 update to its “TSCA Workplan for Chemical Assessments,” a list of 90 chemicals known to pose health risks and that the agency intends to consider for a risk assessment. The list was generated by considering factors that include a chemical’s potential for reproductive or developmental effects, possible neurotoxic or carcinogenic effects, and its ability to persist, bioaccumulate and be toxic.

The TSCA Work Plan list includes a wide range of chemical types, including compounds of heavy metals, such as cadmium, nickel and arsenic, as well as solvents, such as benzene, toluene and xylenes and common monomers, such as vinyl chloride and styrene (see box). The work plan list of 90 chemicals includes four for which EPA has completed risk assessments under the previous legislation: antimony trioxide (a synergist for halogenated flame retardants), trichloroethylene, dichloromethane and HHCB (1,3,4,6,7,8-hexahydro-4,6,6,7,8,8,-hexamethylcyclopenta[gamma]-2-benzopyran; a fragrance ingredient). For those four, previously governed under Section 6 of the TSCA law, EPA plans to publish rules on limiting those chemicals. EPA also has about eight additional chemicals in ongoing safety risk assessments.

Outside organizations have also weighed in on where the agency should start. For example, in July, the EWG published what it feels are the ten highest-priority chemicals for safety risk assessments. The list includes asbestos, bisphenol-A (along with its brominated form), phthalates, two classes of flame retardants (chlorinated phosphate flame retardants and brominated flame retardants), tetrachloroethylene (perchloroethylene), bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (DEHA), and p-dichlorobenzene.

Scott Jenkins

References

1. EPA, TSCA updated workplan 2014. www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-01/documents/tsca_work_plan_chemicals_2014_update-final.pdf

2. EPA, Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act First-Year Implementation Plan, www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/frank-r-lautenberg-chemical-safety-21st-century-act-2

3. Walker, B. and Benesh, M., “10 Chemicals EPA Should Act on Now,” Environmental Working Group, July 2016, www.ewg.org/research/under-new-safety-law-20-toxic-chemicals-epa-should-act-now