Security at many U.S. chemical facilities is regulated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS; Washington, D.C.; http://www.dhs.gov) under the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standard (CFATS). Proposed modifications to this regulation are being debated in the U.S. Congress. In fact, recently, the House of Representatives approved new, stringent standards for chemical site security with the passage of the “Chemical and Water Security Act of 2009” (H.R. 2868).

As they work to comply with CFATS, the chemical process industries (CPI) are keeping a watchful eye on the Congressional proceedings that are leading to proposed changes in the regulation.

CFATS in action

CFATS has come a long way in a short time. The approval of the DHS Appropriations Act in October 2006 gave the DHS authority to regulate the security of high-risk chemical facilities. CFATS, the implementing regulation, was published in April 2007 and its Appendix A, which lists approximately 300 chemicals of interest (COI) and their individual screening threshold quantities (STQ), was published in November of the same year. In May 2009, a document entitled Risk-Based Performance Standards Guidance was published. This guide elaborates on the eighteen risk-based performance standards (RBPSs) that are established in CFATS, and identifies the areas for which a facility’s security will be examined.

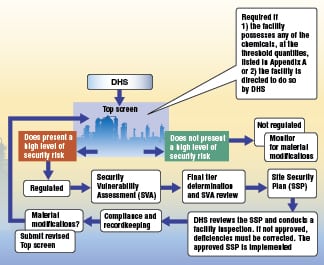

Compliance with CFATS begins with an assessment tool developed by DHS called the Top-Screen, to assist DHS in determining which chemical facilities meet the criteria for being high-risk. Sites possessing chemicals as listed in Appendix A at or above the STQs must submit the Top-Screen questionnaire to DHS for review. As Steve Roberts, an attorney who specializes in CFATS issues (Roberts Law Group PLLC; Houston; http://www.chemicalsecurity.com) explains, those facilities deemed high-level risk are then required to submit a security vulnerability assessment (SVA), after which a facility is categorized into a final risk tier. These facilities must then develop and submit a site security plan (SSP) to DHS within 120 days. DHS will review the SSPs and determine compliance. However, “because the regulations are performance-based and risk-driven, what ‘compliance’ means can change from facility to facility,” says Roberts. He further explains that denial leads to further consultation and “The process of compliance [with CFATS] is continuous as facilities change.” Roberts refers to a chart as a quick summary of the overall CFATS compliance process (Figure 1).

The big issues

There doesn’t seem to be any disagreement among the CPI that security regulations are a good idea. In fact the Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates (SOCMA; Washington D.C.; http://www.socma.com) commended the U.S. Senate for approving legislation that would extend existing chemical security standards for one year. The American Chemistry Council (ACC; Arlington, Va.; http://www.americanchemistry.com) notes that security has long been a priority for its members, who have invested about $8 billion on facility security enhancements under ACC’s Responsible Care Security Code. There also doesn’t seem to be any dissension “on the Hill” about extending CFATS. As she addressed the approximately 350 participants at the 2009 Chemical Sector Security Summit held in Baltimore, Md. on June 29 to July 1, Holly Idelson, majority counsel for the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee put it this way, “The debate is what should the program be, not should there be a program.”

It is expected that in this upcoming year discussions about what a permanent rule should look like will intensify. While the U.S. Senate has not yet formed its own version of a bill, The House of Representatives has proposed a revision to the current CFATS standard. The details are where the dissension begins.

Bill Allmond, vice president of Government Relations and ChemStewards for SOCMA explains that a main point in the House’s bill that SOCMA opposes is mandated inherently safer technologies (IST). IST encompasses a wide breadth of chemical processing procedures, equipment, protection and the use of safer substances. Allmond states that SOCMA “adamantly opposes mandatory IST” and more to the point “What SOCMA opposes the most is getting into [mandatory] chemical substitution.” He explains that SOCMA agrees it is appropriate for DHS to encourage the use of IST, but it should be on a voluntary basis, possibly with incentives (not necessarily financial) to facilities that implement it. A great concern is that a chemical deemed to be a safer alternative might be mandated by government officials without a full understanding of the many ramifications of that chemical substitution.

The ACC also opposes mandatory IST. Scott Jensen, director of communications for ACC says that making IST mandatory in a security regulation brings “discomfort and concern for facility operators since determination is based on one factor, whereas a facility makes that determination based on many factors.” Jensen states simply that ACC’s position is that “it is not necessary to include [mandatory] IST” in the security bill because the current CFATS program allows for and encourages IST implementation.

Integrators and suppliers

As tiered facilities move forward with their site plans, a number of companies are positioning themselves to help with the process of CFATS compliance and implementation. Andrew Wray, senior global marketing manager with Honeywell Process Solutions (Booth 427; Phoenix, Ariz.; http://www.honeywell.com) says that to achieve increasing levels of security, more and more technology needs to be integrated. Honeywell is well-positioned to offer integration with a single system for control, he adds. Looking ahead, Wray says that “as more and more systems are integrated into the network, more products need to make decisions ‘at the edge’.” To explain what he means by at the edge, Wray gives the example of a card reader at a facility perimeter. While the card reader likely has local decision-making capabilities, new technology is emerging that will check the integrity of the reader’s data prior to gaining access to the network.â– Dorothy Lozowski

For more, see the complete article, Chemical Plant Security, Chemical Engineering, September 2009, pp. 21–23.