Transparent polymer film started with an accident . . . and spurred a packaging revolution

One night in Paris, in 1900, Swiss chemist Jacques Brandenberger was enjoying dinner in a restaurant when he noticed that a fellow patron had spilled a glass of wine. As waiters scrambled to clear the table, it occurred to Brandenberger that the process of removing and replacing the soiled tablecloth was time-consuming and inefficient. He began to mull an application of research he had been conducting into the organic polymer cellulose. Brandenberger conjectured that he could spray liquid viscose, created from natural sources of regenerated cellulose, onto fabric and thereby create waterproof coatings for tablecloths and other textiles.

Brandenberger’s initial experiments in this vein were promising, but ultimately disappointing. The fabric coatings he produced were indeed waterproof, but the coatings proved far too stiff to maintain fabric pliability. But Brandenberger noticed something of interest: the coatings could be peeled off the fabrics without difficulty, yielding a thin, diaphanous film. He began to conceive that the value in his material lay not only in its water resistance but also in its transparency.

Commercial juggernaut

By 1912, having enhanced his material (especially through the addition of glycerin, to soften it), Brandenberger had patented his product and designed a manufacturing process for it, selling the commercial rights to the firm Comptoir des Textiles Artificiels (CTA). Brandenberger called the film “Cellophane,” a portmanteau of cellulose and the French word diaphane, meaning transparent. The early adopters of this transparent film were food product manufacturers, such as the American candy manufacturer, Whitman’s, which was a major customer by 1912. Companies like this recognized cellophane’s potential to revolutionize the packaging and retailing of perishable consumer goods.

Intrigued by the vast potential of this product, the DuPont company purchased the exclusive rights to make and sell cellophane in the U.S. in 1923. In 1924, DuPont chemist William Hale Church reformulated the transparent film, developing a nitrocellulose lacquer that rendered it not only waterproof but more moisture-proof, enhancing its fresh-food preservation properties.

DuPont’s innovations also extended to production. Initially, making cellophane required the time-consuming dissolution of cellulose from materials like wood, celery or cotton in alkali and carbon disulfide to make viscose, prior to taking the liquid to a cellulose state via an acid bath. Within a few years, however, DuPont had invented machines that enabled the mass production of cellophane, ensuring a vast supply for what would become a booming packaging market. Indeed, these developments catalyzed explosive growth of DuPont’s sales of cellophane to food manufacturers — between 1928 and 1930, sales of cellophane tripled. By 1938, the “magical” transparent film accounted for 10% of DuPont’s sales and 25% of its profits. The product you could “see right through” had become a commercial juggernaut.

Cellophane’s emergence as a packaging innovation for the consumer market coincided with, and encouraged, the rise of self-service retailing, particularly of food products. In the early 20th century, customers typically purchased fresh foods from open-air markets, where quality was uneven and food waste high. Grocers sold customers canned products, or fresh foods that were selected and wrapped by store clerks. The introduction of cellophane wrapping, especially when coupled with refrigerated store shelving, allowed sellers to present fresh goods in packaging that connoted cleanliness, enhanced food safety and quality control, reduced ambient odors, and allowed for buyer’s easy access without the involvement of a clerk.

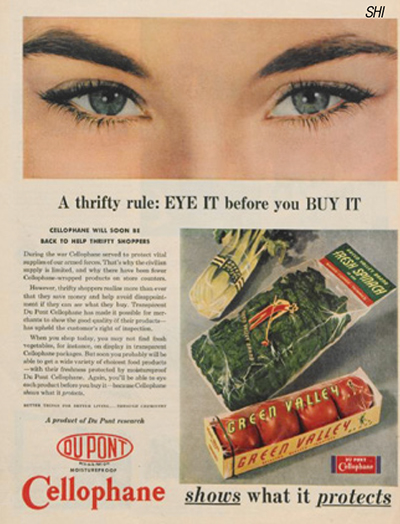

Most significantly, cellophane enabled consumers to see what they were buying and to make purchasing decisions based on visual inputs such as colors, textures and evident freshness. DuPont’s own consumer research found that 85% of food purchasing decisions were made by customers visually scanning products in store. Advertising of the period encouraged shoppers, bluntly, to “eye it before you buy it” (Figure 1). And when developments to cellophane and competing products in the 1940s ensured that meat could be wrapped to allow for an optimal balance between moisture control and oxygen penetration, the provision of fresh red meat outside the butcher’s counter further ensured cellophane’s packaging dominance.

FIGURE 1. A 1945 magazine advertisement touts the transparent property of cellophane biopolymer

This dominance did not survive the 20th century. Cheaper, petroleum-based films, such as polyethylene for baked goods and polyvinyl chloride for meat packaging, gradually ate into wood-based cellophane’s market share. By the 1980s, production of cellophane was almost halted. But in recent years, cellophane production has enjoyed a modest resurgence. Its complete biodegradability stands in contrast with the plastic products that, in the minds of consumers, fill landfills, allowing consumers to “eye it before they buy it,” in a new way.

Edited by Scott Jenkins

Editor’s note: This content is created by the research and curation team at the Science History Institute (SHI; Philadelphia, Pa.; www.sciencehistory.org).