Security at many U.S. chemical facilities is currently regulated by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS; Washington, D.C.; www.dhs.gov) under the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standard (CFATS). This rule, however, is about to expire this month, October 2009. All expectations are that CFATS will be extended for a year, while proposed modifications to the standard continue to be debated in the U.S. Congress.

As they work to comply with CFATS, the chemical process industries (CPI) are keeping a watchful eye on the Congressional proceedings that are leading to proposed changes in the regulation.“CFATS — it is by far the most dramatic issue affecting chemical plant security today,” notes Robert Hile, director of integrated security solutions at Siemens Building Technologies, Inc. (Buffalo Grove, Ill.; www.usa.siemens.com/security).

CFATS in action

CFATS has come a long way in a short time. The approval of the DHS Appropriations Act in October 2006 gave the DHS authority to regulate the security of high-risk chemical facilities. CFATS, the implementing regulation, was published in April 2007 and its Appendix A, which lists approximately 300 chemicals of interest (COI) and their individual screening threshold quantities (STQ), was published in November of the same year. In May 2009, a document entitled Risk-Based Performance Standards Guidance was published. This guide elaborates on the eighteen risk-based performance standards (RBPSs) that are established in CFATS, and identifies the areas for which a facility’s security will be examined, such as perimeter security, access control, personnel surety (a check on personnel credentials) and cyber security.

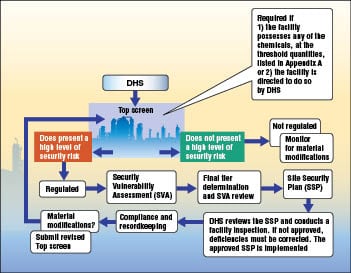

Compliance with CFATS begins with an assessment tool developed by DHS called the Top-Screen, to assist DHS in determining which chemical facilities meet the criteria for being high-risk. Sites possessing chemicals as listed in Appendix A at or above the STQs must submit the Top-Screen questionnaire to DHS for review. As Steve Roberts, an attorney who specializes in CFATS issues (Roberts Law Group PLLC; Houston; www.chemicalsecurity.com) explains, those facilities deemed high-level risk are then required to submit a security vulnerability assessment (SVA), after which a facility is categorized into a final risk tier. These facilities must then develop and submit a site security plan (SSP) to DHS within 120 days. Roberts says that the first 140 or so “final tier letters” were sent out in May 2009, followed by about another 400 in June. More tier letters are forthcoming. Those companies in receipt of the letters are now in the stage of submitting their SSPs. DHS will review the SSPs and determine compliance. However, “because the regulations are performance-based and risk-driven, what ‘compliance’ means can change from facility to facility,” says Roberts. He further explains that denial leads to further consultation and “The process of compliance [with CFATS] is continuous as facilities change.” Roberts refers to a chart as a quick summary of the overall CFATS compliance process (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. The CFATS process is summarized in this flowchart

Source: Roberts Law Group PLLC

|

The big issues

There doesn’t seem to be any disagreement among the CPI that security regulations are a good idea. In fact the Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates (SOCMA; Washington D.C.; www.socma.com) commends the U.S. Senate for approving legislation that would extend existing chemical security standards for one year. The American Chemistry Council (ACC; Arlington, Va.; www.americanchemistry.com) notes that security has long been a priority for its members, who have invested about $8 billion on facility security enhancements under ACC’s Responsible Care Security Code. In a recently issued statement, Marty Durbin, ACC’s vice president of Federal Affairs says, “We believe the ongoing implementation of the Chemical Facility Anti-Terrorism Standards demonstrates a smart and aggressive approach to both securing and protecting the economic viability of this essential part of the nation’s infrastructure.”

There also doesn’t seem to be any dissension “on the Hill” about extending CFATS. As she addressed the approximately 350 participants at the 2009 Chemical Sector Security Summit held in Baltimore, Md. on June 29 to July 1, Holly Idelson, majority counsel for the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee put it this way, “The debate is what should the program be, not should there be a program.” Ms. Idelson made it clear that as the Senate committee works on defining what the program should be, it welcomes input from the CPI to let the members know what is working and what is not working in CFATS, saying, “Our [the Senate Committee’s] door is open.”

Since the clock has just about run out for a standalone security bill this year, CFATS is well on its way to a one-year extension. It is also expected that in this upcoming year discussions about what a permanent rule should look like will intensify. While the U.S. Senate has not yet formed its own version of a bill, The House of Representatives has proposed a revision to the current CFATS standard. The details are where the dissension begins.

Bill Allmond, vice president of Government Relations and ChemStewards for SOCMA explains that the two main points in the House’s bill that SOCMA opposes are: 1) mandated inherently safer technologies (IST); and 2) a civil suits clause.

IST encompasses a wide breadth of chemical processing procedures, equipment, protection and the use of safer substances. Allmond states that SOCMA “adamantly opposes mandatory IST” and more to the point “What SOCMA opposes the most is getting into [mandatory] chemical substitution.” He explains that SOCMA agrees it is appropriate for DHS to encourage the use of IST, but it should be on a voluntary basis, possibly with incentives (not necessarily financial) to facilities that implement it. SOCMA’s opposition to mandatory IST is founded on several fronts. First, IST within a security framework is already addressed by two other well-entrenched regulations: 1) the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Risk Management Program Rule (RMP); and 2) the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Admin.’s (OSHA) Process Safety Management Regulation. A great concern is that a chemical deemed to be a safer alternative might be mandated by government officials without a full understanding of the many ramifications of that chemical substitution.

Allmond uses manufacturers of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) as an example of where unexpected complications could arise. API manufacturers go through a lengthy process of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals. If, for example, a so-called “safer alternative” compound were mandated, this new compound might require an untenable amount of retesting before the switch could occur, and it might not be approved by the FDA.

The ACC also opposes mandatory IST. Scott Jensen, director of communications for ACC says that making IST mandatory in a security regulation brings “discomfort and concern for facility operators since determination is based on one factor, whereas a facility makes that determination based on many factors.” Jensen states simply that ACC’s position is that “it is not necessary to include [mandatory] IST” in the security bill because the current CFATS program allows for and encourages IST implementation.

Both SOCMA and the ACC also oppose the civil suits clause in the House’s proposed legislature, which would allow any citizen to sue a company if their perception is that the CFATS regulation is not being followed. Jensen says that the ACC feels adamantly that it is not necessary for courts to get involved. SOCMA’s Allmond notes that a citizen suit provision is common in environmental law, but it doesn’t even seem feasible in a security framework since the details of a facility’s security plan would not be accessible to the public because they are deemed CVI (chemical-terrorism vulnerability information), which is confidential and known only to DHS and designated facility employees.

While the IST and civil suits issues are the main areas of disagreement between the organizations representing the CPI and the proposed House bill, there are other areas of discussion. These questions include who should be covered in CFATS, such as when it comes to water-treatment facilities and industrial versus agricultural uses of ammonium nitrate. ACC’s Jensen puts it into perspective, though, when he says, “We [the CPI, U.S. Congress and DHS] agree on more than we disagree” including the overall objective of having permanent Federal chemical security regulations.

Integrators and suppliers

As tiered facilities move forward with their site plans, a number of companies are positioning themselves to help with the process of CFATS compliance and implementation. Hile says that Siemens can help “from start to finish”, offering “assistance from the very early stages all the way through to the implementation.” One form of assistance is a survey package that helps to break down CFATS into “layman’s” terms giving a facility a sort of template to help form the SVA, and then further down the line to help with the plan (SSP). Siemens is poised to offer an array of surveillance products and perimeter-intrusion-detection systems. The majority of RBPSs in CFATS deal with the physical security of a site, so these types of products are expected to be an important part of a site’s security plan.

Andrew Wray, senior global marketing manager with Honeywell Process Solutions (Phoenix, Ariz.; www.honeywell.com) says that to achieve increasing levels of security, more and more technology needs to be integrated. Honeywell is well-positioned to offer integration with a single system for control, he adds. Looking ahead, Wray says that “as more and more systems are integrated into the network, more products need to make decisions ‘at the edge’.” To explain what he means by at the edge, Wray gives the example of a card reader at a facility perimeter. While the card reader likely has local decision-making capabilities, new technology is emerging that will check the integrity of the reader’s data prior to gaining access to the network.

“Integration of multiple technologies is key,” agrees Ryan Loughin, director of the Petro-Chem and Energy Div. of ADT Advanced Integration (Norristown, Pa.; www.adtbusiness.com/petrochem-ce). He goes on to say that “The overall security philosophy at a plant is changing. Security is now a program much like safety has been for years…CFATS is driving this program-related process.” Loughin explains that a tiered facility faces two basic threats: toxic release, and theft and diversion. ADT’s approach to working with a facility with one or both of these threats is to consider three key factors: deter, detect and delay. “Many of the technologies being used on these facilities have been around for some time, but never utilized in the private sector the way they are now,” says Loughin as he gives examples of fiber-based fence detection, thermal imaging, video analytics and radar. “I believe the day of the six-foot chain-link fence is over for the highest-risk facilities,” he says, citing that K-rated and high-security-fencing and barrier technology are now being used (Figure 2). Loughin notes that ADT has Safety (Support Anti-terrorism by Fostering Effective Technologies) Act Certification for electronic security services. This DHS-designated certification is a way to manage the risk of liability, says Roberts, who advises companies to consider Safety Act protection as a factor when selecting a security vendor during the procurement process.

The cyber side

While the bulk of CFATS focuses on the physical plant, it also addresses cyber security, which is undoubtedly an integral part of overall security. Part of the issue with regulating cyber security is how to quantify what level of cyber security one needs, or has. Experts are using their experience with safety standards to focus on this issue.

In the safety arena, metrics can be assigned according to probability on a scale of safety integrity levels (SILs; see CE, Sept. 2007, pp. 69–74). Assigning metrics to security, however, poses a bigger challenge. As Eric Cosman, co-chair of the ISA99 Committee and who works at the Dow Chemical Co. puts it, “In security you have a purposeful, intelligent adversary. How do you measure that?” Still, Cosman and his colleagues on the ISA99 Committee, with contributions from other groups, such as ACC’s Chem ITC, are making headway in defining cyber-security standards that will be applicable to a broad industry base. A concept gaining momentum is the development of security assurance levels (SALs), comparable to SILs. Cosman says that the “SAL concept has a lot of promise. It is going to get us somewhere, I just don’t know how far.”

John Cusimano, director of security solutions for exida (Sellersville, Pa.; www.exida.com) explains that it has been a long process, but the IT security and control-system communities have successfully cooperated to develop cyber standards and methodologies, and that “Recently the safety system community has joined this effort, bringing [its] proven risk-mitigation engineering methods to the table.” Among other services, exida offers a Control System Security Assessment to review the cyber-security environment of a facility and compare it with industry best practices with recommendations to address possible gaps. As momentum increases in the efforts to standardize cyber security, everyone seems to agree in the prediction that it will become a more integral part of future security regulations. â–

Dorothy Lozowski